Design and Making as a Means to Understand the Past

From Prototype to Pitch: New Pathways in Design, Maker and Entrepreneurship Education.

Design and Making as a Means to Understand the Past

by Elaine Chu, Jessie Kirk, and Mark Silberberg

Abstract

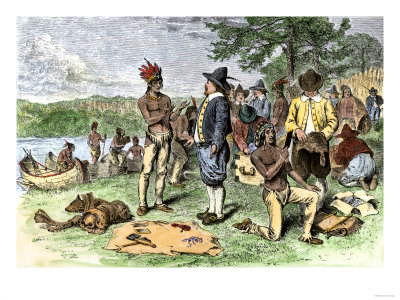

In this chapter, we explore how the essential practices associated with design, making and entrepreneurship are embedded directly into the fabric of the curriculum and the classroom at the Little Red School House & Elisabeth Irwin High School (LREI). Specifically, we describe the journey our third grade students take as they explore the early history of Manhattan and its people, the interactions between the Lenape and Dutch settlers, and the implications that this history has on students’ visions for the future of our city. This work was born out of an iterative process that began with the questions, “How might we design for an experience that places students on the inside of an historical narrative?” “How might we experiment with scale so that instead of making and building models that tell a story from the outside students are able to live and learn within the model itself?” And “How might students’ experience with design and making lead them to discover a sense of agency and purpose in the world beyond school?” At LREI, teachers are experienced designers deeply committed to a human-centered approach to pedagogy. The emergence of design, making and entrepreneurship have the potential to expand this crucial dimension of teaching into more classrooms and schools. It is our contention that the most important place to begin this transformation is in the classroom itself.

Introduction

For progressive schools in general and for the Little Red School House in particular, the emergence of design, making, and entrepreneurship as mindsets for learning have helped to amplify many of the core values (e.g,. critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, courage) that have always been central to our practice. One has only to look beneath the surface of what many are calling essential “21st Century skills” to find the solid foundation of progressive practice on which these “new” ideas rest. That said, the current moment has provided learners, both young and old, and the schools in which both work with useful systems to help frame the process of experience and inquiry that is essential for learning. We see design, making and entrepreneurship as a set of related inquiry tools that are available to learners as they set out to construct knowledge and wisdom. They allow for an investigation of experience that is grounded in empathy, iteration, the construction of personally/socially relevant products, and the agency that comes from working towards solutions to authentic and meaningful problems.

As Agnes De Lima observed in 1942 in The Little Red School House:

The general education aim . . . will be achieved, not through a routine process of instruction, but through a series of experiences, which will awaken the interest in the children and develop a facility for meeting individual and social situations… We believed in the beginning as we still do that children can be happy in school, that education must be thought of in terms of growth and comes by experiencing rather than by mere learning, and that life does not begin when school ends but rather, as John Dewey says, that school is life.” (pp. 3 and 5)

The ideas that are central to this chapter and this book derive their power precisely from the fact that they seek to open the place called school to the larger world in which it is situated. As we work to ensure that the activity of school is not only purposeful, but draws on the power and agency that students bring with them to school, we also understand our obligation to narrow the distance between the classroom and the wider world to which it is connected. To move schools in this direction, teachers cannot simply embrace (or be mandated to embrace) design, making and entrepreneurship as some new program to be added to the curriculum. These ideas must come to be seen as a framework for supporting a reflective and forward thinking practice. The best teachers have always been designers. For these teachers, the curriculum at any given moment is simply the most current iteration of a project that seeks to best meet the learning needs of a particular group of students. In essence, this chapter was born out of an iterative process that began with the questions, “How might we design for an experience that places students on the inside of an historical narrative?” “How might we experiment with scale so that instead of making and building models that tell a story from the outside students are able to live and learn within the model itself?” And “How might students’ experience with design and making lead them to discover a sense of agency and purpose in the world beyond school?”

Seen in this light, our curriculum is always in flux and being “made.” We would also argue that the curriculum is something more than a scope and sequence of content and skills. In fact, we are living in a moment where what many schools have long considered the “curriculum” can be accessed more easily and reliably through resources available on the Internet. For us then, the curriculum is the activity that guides learners into an experience and serves as a roadmap for possible pathways through that experience. Some of these pathways may have been traveled before by earlier groups of learners and some will be discovered for the first time as learners bring their own prior experiences to this new context. While teachers must bring deep content knowledge and an equally deep understanding of children to their work, these are necessary, but not sufficient, dispositions for the work of teaching. Progressive schools have always seen the teacher as an experienced designer deeply committed to a human-centered approach to pedagogy. The emergence of design, making and entrepreneurship are helping to expand this crucial dimension of teaching into more classrooms and schools. As De Lima notes,

“We are, then, concerned in our curriculum to make sure that it affords the kind of experiences and the kinds of activities which will help children to grow normally and naturally. The old-line pedagogue was continually asking, What must a child know, what knowledge is of most worth? We ask instead, What should a child be like, what ways of acting and what habits of response are most worth while? But we do not consider the child alone, for naturally the individual is part of a larger group and this group part of a wider community. Our school is neither child-centered nor society-centered. Rather we take the child as he is and where he is, try to understand him, and then seek to help him understand the kind of world in which he lives and the part he is to play in it.” (p. 17)

We have tried in this chapter to capture how the essential practices associated with design, making and entrepreneurship can be embedded directly into the fabric of the curriculum and the classroom. Specifically, we describe the journey our third grade students take as they explore the early history of Manhattan and its people, the interactions between the Lenape and Dutch settlers, and the implications that this history has on students’ visions for the future of our city. While we see the value that lies in creating specific named learning spaces to support this kind of work, we worry that in some schools the rush to create Maker Spaces, Fab Labs and Design Studios may actually limit the transformation that is desperately needed in too many of our nation’s classrooms. Ideally, the boundaries between these spaces must be permeable so that opportunities for exploration and discovery can emerge in the context of student-driven interests and concepts and ideas that the community has decided are worth exploring together. Moreover, given the constraints that many schools face in attempting to create designated spaces for design, making and entrepreneurship, we would make the argument that the most important place to begin this transformation is in the classroom itself.

“We not only study history—

we make it.

We not only live life—

we enjoy living it.

We need hope;

we need strength;

we need imagination.”

—Agnes De Lima in The LIttle Red School House (p. 27)

CREATING SOCIAL SCIENTISTS: Thinking like an Archaeologist

“TIME TRAVEL TO THE PAST. 1, 2, 3, LET’S MOVE FAST. SO MUCH TO LEARN, AND LOTS TO SEE. TIME TRAVEL, 1, 2, 3!”

What’s the best way to study the past? Is it to read books and articles? To study photographs and artifacts? To use the internet and do research? These tools alone failed to achieve what we really wanted: that students living in New York City in 2016 could walk right into the past and see and feel it for themselves. We found the perfect solution: time travel (see glossary). We could give our students the experience of living long ago, but once there, then what? How do you make sense of history? First, we needed to teach the specific skills for thinking about the past.

How does a social scientist think?

How does a social scientist think?

We teach our students to assume the mindset of an archaeologist. How do we learn about the past using primary source materials, such as artifacts, pictures and documents? Students make careful and detailed observations, and speculate using evidential reasoning. They begin making a picture of the past: Who could have used the object? For what purpose? Where? When? What does it tell us about life at that time? Once they know how to study one “Mystery Object,” they are given the task of looking at a collection of artifacts that they must put together to make a picture of a “Mystery Time and Place.” The emphasis is not on naming the time and place, but on understanding how people lived then and there. (See Note 1)

Figuring out the “Mystery Time and Place” from the clues provided is an exciting puzzle that mimics the authentic work of archaeologists. Once our students have practiced these skills, we provide a compelling narrative within which they can use them. Using an imaginative inquiry (see glossary) framework, the students are enlisted as archaeologists who receive a shipment of artifacts that they must analyze to create dioramas for the American Museum of Natural History. We raise the stakes even further. Succeeding at this task leads to the opportunity to apply to be on a secret team of experts who must study the history of New York City in order to save its future. As members of this “Team X” (see Note 2) students are motivated to learn about their city’s history for the real purpose of making it better (see Note 3). And they must do it together.

Empathy at the Center

In all phases of their work, students seek to understand what it means to think, feel, see and know from the perspective of another. Nowhere is this more important than at the start of the inquiry/design process. As students/designers seek a more empathic connection with their work, they are better able to recognize their own biases and assumptions. They are also better able to see how these dispositions can inform and also interfere with efforts to understand the other and her experiences and needs. This developing sense of self-awareness and the parallel recognition of the wants and needs of others is crucial for the young designer and maker.

CREATING A CONTEXT: Thinking like a Lenape

“Come gather in the longhouse to hear the Elder’s vision from last night…”

Third graders gather in a circle around the firepit. The villagers are presented with the Elder’s vision and discuss what it means: the Big Hunt is approaching. Our Lenape village must plan what to do.

Villagers share their ideas for what we need to do first, what tools are needed, what animals to hunt and where to find them. Most students have the same response: “We’ll use bows and arrows!”

We encourage them to think through other ways to catch game and the steps involved: “Where will you get your bows and arrows? Where will you find the animals? Is that the only way to hunt? Are there other ways to catch animals in the wild?” These prompting questions push them to think beyond their initial assumptions about what hunting is.

At this point we don’t expect students to have any knowledge about Lenape hunting, but to use their knowledge about the world and what they know so far about Manhattan in the 1500s to imagine what they would do as a Lenape in this situation. We intentionally present them with this authentic problem before they have been given any information — not to stump them or force them to guess — but to activate their innate ability to use logic and their existing experiences to problem-solve.

At this point we don’t expect students to have any knowledge about Lenape hunting, but to use their knowledge about the world and what they know so far about Manhattan in the 1500s to imagine what they would do as a Lenape in this situation. We intentionally present them with this authentic problem before they have been given any information — not to stump them or force them to guess — but to activate their innate ability to use logic and their existing experiences to problem-solve.

A Problem Worth Solving

Too often the value of a problem is only obvious and compelling to the teacher. For the student, the problem is a task relegated to that domain called schoolwork. A design and making ethos helps to create a space for students to see their own needs and interests reflected in a particular problem and helps to turn schoolwork into “life work.” When the context for learning is framed in terms of a problem worth exploring, the classroom itself undergoes a transformation as students and teachers share in the possibilities for new experience and new learning.

What students have gotten prior to this lesson is a context for thinking like a Lenape. They have learned about the environment that the Lenape lived in, what resources were available then, and how they lived together as a community. Over the past several weeks, our students have been given a name by the Name Giver, identified themselves as a member of the Turkey clan, lashed saplings together and tied on bark shingles to make a longhouse, and went through the steps of skinning, tanning and sewing hides to make their clothing. In short, they have been living like a Lenape (see Note 4).

What students have gotten prior to this lesson is a context for thinking like a Lenape. They have learned about the environment that the Lenape lived in, what resources were available then, and how they lived together as a community. Over the past several weeks, our students have been given a name by the Name Giver, identified themselves as a member of the Turkey clan, lashed saplings together and tied on bark shingles to make a longhouse, and went through the steps of skinning, tanning and sewing hides to make their clothing. In short, they have been living like a Lenape (see Note 4).

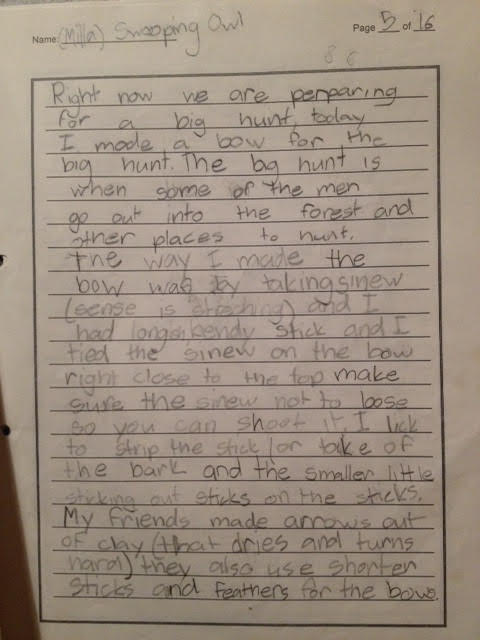

With this framework for thinking about the past as someone living back then, students are ready to learn more specific information about the various hunting methods, tools, and steps that the Lenape used. They read a detailed article and study pictures of tools and traps. By the next day, they are prepared to apply their working knowledge to making plans for their hunt. Small groups are assigned different hunting methods to work on and then come together for feedback and input from the whole class. The previous days’ tasks of thinking through the various aspects of the problem (what to hunt, where, how), and research about Lenape hunting have prepared them to make detailed, informed blueprints.

Prototyping to Understand

It is here that students begin to explore their questions through work with materials and making. This process helps them to distill key ideas down to their essence so that what is being made can speak to the underlying meaning of the experience. For example, through the act of making the longhouse, the student not only enters into a relationship with the materials, but also sees her relationship to the Lenape and the meaning of the longhouse in a different light. The work is also iterative as students are not simply following a set of instructions. They are learning through the limits imposed by the materials. Most first attempts at making don’t solve the problem, but they do suggest possible next steps (i.e., “This snare design seems to work better.). The work here is purposeful as ideas and understandings are made manifest through the act of making.

Now it’s time to make what we need and go on the hunt. The “men” work together to make bows, arrows, and quivers, while the “women” prepare racks for drying and smoking the meat that will be brought home. (Our students know that in drama they may be asked to take on the role of either gender.) Sticks, clay, twine, leather, and construction paper have been provided for this purpose. Our goal is to give students materials that will allow them to replicate the process of making these tools. For example, they can shape clay into arrow heads that they will lash onto sticks, whereas rocks cannot be easily shaped and paper is two-dimensional.

Now it’s time to make what we need and go on the hunt. The “men” work together to make bows, arrows, and quivers, while the “women” prepare racks for drying and smoking the meat that will be brought home. (Our students know that in drama they may be asked to take on the role of either gender.) Sticks, clay, twine, leather, and construction paper have been provided for this purpose. Our goal is to give students materials that will allow them to replicate the process of making these tools. For example, they can shape clay into arrow heads that they will lash onto sticks, whereas rocks cannot be easily shaped and paper is two-dimensional.

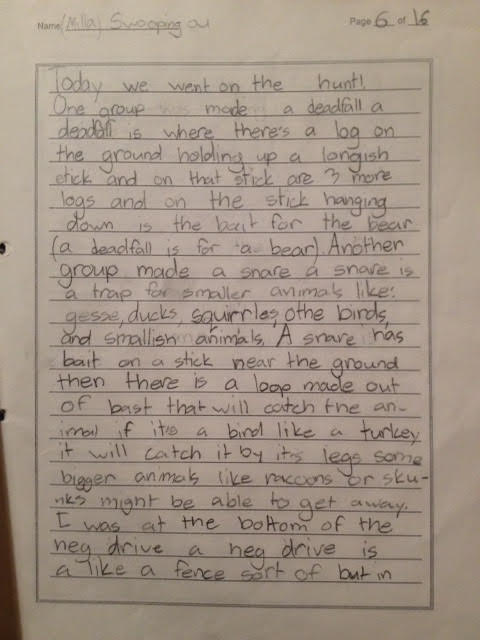

The Big Hunt begins in the longhouse. We pray to the Mesingw, the spirit who protects the animals of the forest. Then we begin our long trek to various habitats (forest, wetlands, etc.) where each group finds animal tracks in different parts of the room. They need to identify the animal and figure out what method would be the most suitable for hunting it. They proceed to build their traps and snares using materials they find at their site.

There is no prescribed way to do this. All that students have available to them is the working knowledge they have built over the last few days from articles, pictures, and discussions, and basic materials that we have given them to represent the logs, saplings, bark, and sinew that were available in the wild. Even after several days of talking and thinking about how to hunt an animal, students are now confronted with the reality of having to actually do it. How can you get the spring action of a snare to work? Where do you put the bait so that it will trigger the trap to fall? How can you get a group of deer to all run in the same direction towards waiting hunters? In this moment, they are forced to put their designs into action. There is trial and error, they may or may not succeed, but either way they are gaining a deeper understanding of the particular system they are working on.

There is no prescribed way to do this. All that students have available to them is the working knowledge they have built over the last few days from articles, pictures, and discussions, and basic materials that we have given them to represent the logs, saplings, bark, and sinew that were available in the wild. Even after several days of talking and thinking about how to hunt an animal, students are now confronted with the reality of having to actually do it. How can you get the spring action of a snare to work? Where do you put the bait so that it will trigger the trap to fall? How can you get a group of deer to all run in the same direction towards waiting hunters? In this moment, they are forced to put their designs into action. There is trial and error, they may or may not succeed, but either way they are gaining a deeper understanding of the particular system they are working on.

Teaching as an Iterative Process

This early stage prototyping work being carried out by the students also informs the teacher’s thinking. We have chosen certain materials to represent what would be “found” in the field because they are easier for the students to use. And we wonder if it might make more sense to have students explore the actual materials first so that there is some understanding of the complexity/craftsmanship associated with this work. Perhaps this “empathy” for the materials themselves might then carry over into the design/making with more “modern” materials. This early encounter with materials would encourage students to ask questions like, “How might I use the materials that are available to me to communicate something of the experience/story of work with the more traditional and historically accurate materials?” In this way, when the student talks about what he has made, he can, for example, more easily refer to the clay as stone.

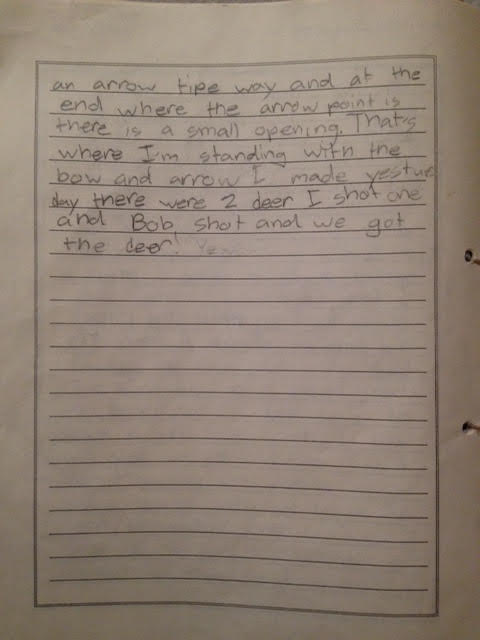

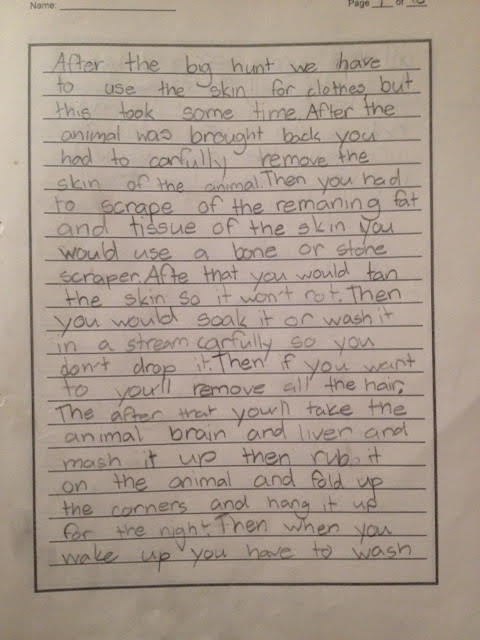

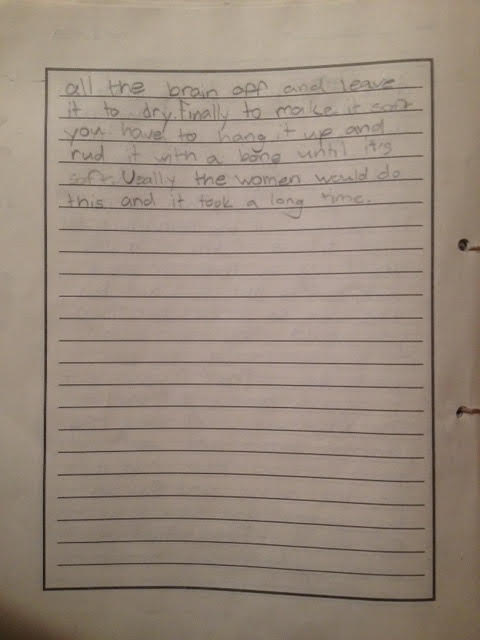

To complete the full arc of the hunting process, we return to the village with our game, which is then cleaned, skinned, the hides tanned and the meat smoked and dried. We celebrate and give thanks to the spirits for our bounty. Our students have not just researched Lenape hunting, but they have experienced the many layers and complexities of it. They write in their Lenape journals about their experiences.

To complete the full arc of the hunting process, we return to the village with our game, which is then cleaned, skinned, the hides tanned and the meat smoked and dried. We celebrate and give thanks to the spirits for our bounty. Our students have not just researched Lenape hunting, but they have experienced the many layers and complexities of it. They write in their Lenape journals about their experiences.

Designing with Others in Mind

As students continue to develop empathy for the experience of the Lenape and Dutch settlers, they now need to expand that view to include the other students, teachers and families who will visit their museum. This shift asks them to see their own learning in a different light. As the student-designer becomes curator, she must make explicit aspects of her learning that she cannot assume the visitor will share. The student asks, “How can I design this space so that it best tells the story of what I have learned?” And “How can I do this so that I do not have to step out of my character to explain things to my audience?”

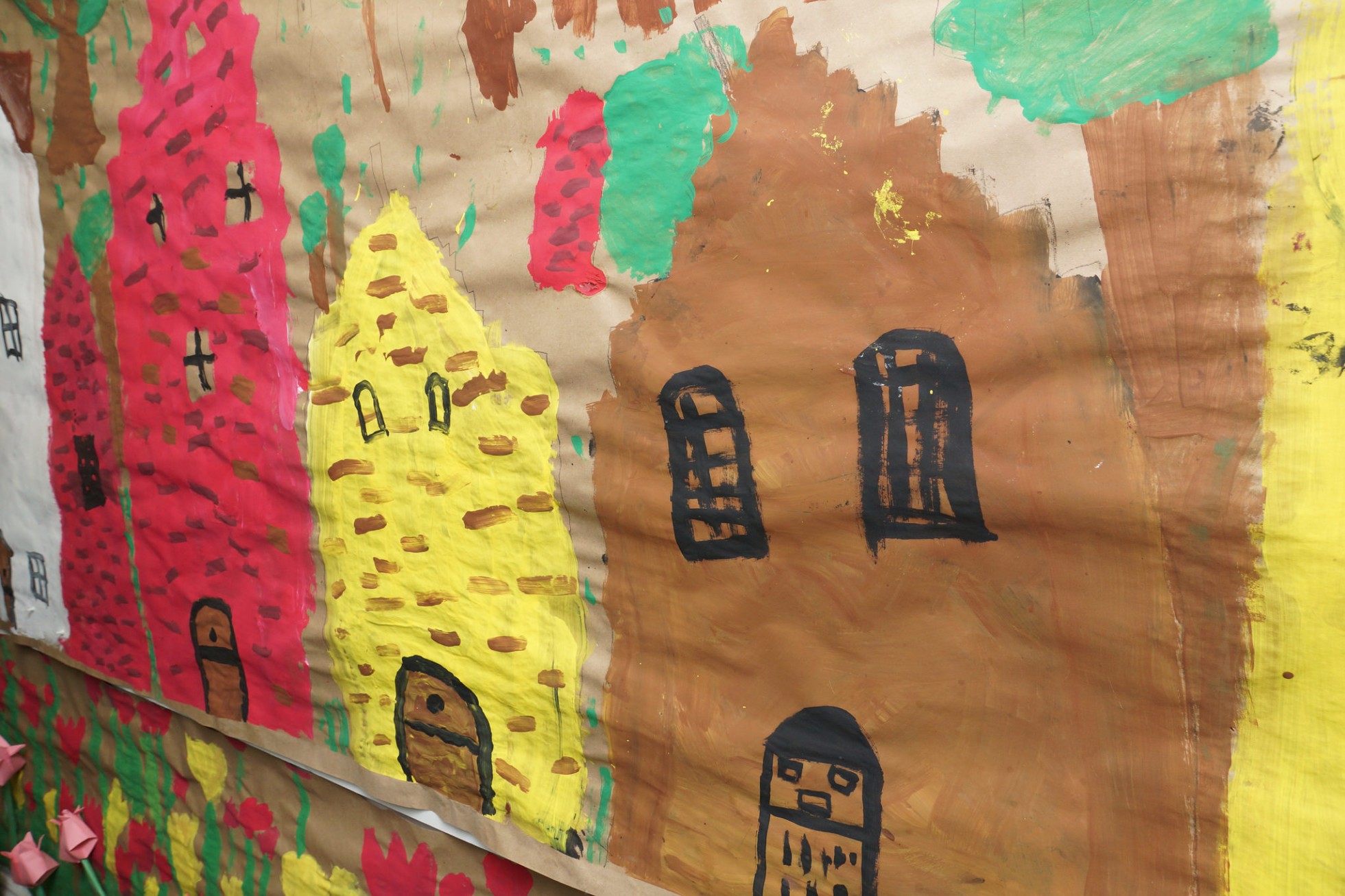

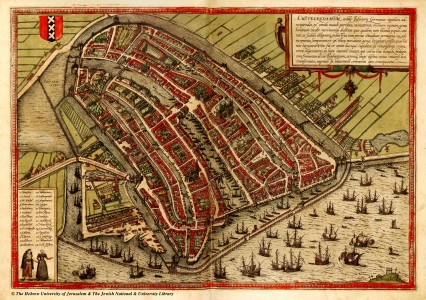

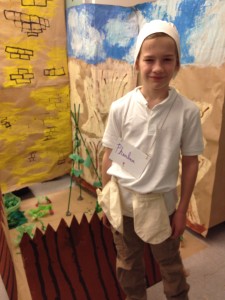

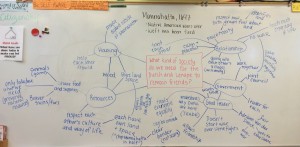

CREATING AN ENVIRONMENT: Building Mannahatta

“What do we want to teach about the daily life of the Lenape and Dutch colonists?” This is the question that prompts our students to begin building a life-size model that transforms our classrooms into an interactive museum mid-year. We recreate the world of the past — this time not for students to experience the routines and struggles of long ago as they have been doing up until now, but as a platform for conveying their knowledge to others. A new element is introduced to their learning: an audience. We ask them to do this by replicating the environment of Mannahatta, c. 1630: a Lenape village and longhouse in one classroom, and the streets of New Amsterdam and Dutch colonist’s home in the other.

“What are the different parts that make up the Lenape or Dutch colonial community and way of life?” In answering this, our students are encouraged to think about what they know about the various aspects that make up a society: housing, food, clothing, jobs, family, education, religion, and natural environment. The goal of this project is for our students to put together the whole picture of daily life in these two communities. In small groups, students focus on one category. “What is important to teach about your topic?” They think about the big ideas, not just what they want to make, drawing from knowledge they have constructed over the past few months. They are not only using facts and information they have learned, but are also reflecting on their “direct” experiences of living like a Lenape or Dutch colonist, and thinking about what it means and why it’s important. “When you were making a trap as a Lenape hunter, what did you learn about Lenape food that you think is important to teach others?” Students must think about why and how people lived as they did and how those activities functioned together to form a working society.

“How will you show your topic? What will you make?” Here, our students know what to do. At this point, they have already built parts of a longhouse, made traps and snares, made Dutch meals, dipped candles, painted Delft tiles, etc. They have also envisioned the scenery and landscape, as well as the daily routines and interactions from “time-traveling” to the past. Students are not simply repeating what they have already done; there is a repurposing and expansion of previous ideas. Whereas they previously made tools and traps to learn about Lenape hunting, now they need to show the larger system of how Lenape hunting works, for example: the various methods, tools, habitats, prey, etc. They are designing and making with the purpose of expressing their knowledge to others.

“How will you show your topic? What will you make?” Here, our students know what to do. At this point, they have already built parts of a longhouse, made traps and snares, made Dutch meals, dipped candles, painted Delft tiles, etc. They have also envisioned the scenery and landscape, as well as the daily routines and interactions from “time-traveling” to the past. Students are not simply repeating what they have already done; there is a repurposing and expansion of previous ideas. Whereas they previously made tools and traps to learn about Lenape hunting, now they need to show the larger system of how Lenape hunting works, for example: the various methods, tools, habitats, prey, etc. They are designing and making with the purpose of expressing their knowledge to others.

“How will you make what you need and what materials will you use?” At this stage, the classroom becomes a maker space, as students try to bring the past to life. They have to creatively use what is available to them. “How can I build a drying rack that will stand up on a classroom floor?” “How can we make a Dutch alcove bed, when it was built into the wall?” While they have been able to imagine the world of Mannahatta right in their own classrooms, now they need to actually make it. They grapple with constructing stationary objects and backdrops to represent something dynamic and moving, i.e. a way of life. “How can we show how the gears, shafts, millstones, etc. work together to grind wheat when our windmill is painted on the wall?” “How do we teach about Lenape religion when their beliefs reached all areas of their lives and influenced everything they did?”

“How will you make what you need and what materials will you use?” At this stage, the classroom becomes a maker space, as students try to bring the past to life. They have to creatively use what is available to them. “How can I build a drying rack that will stand up on a classroom floor?” “How can we make a Dutch alcove bed, when it was built into the wall?” While they have been able to imagine the world of Mannahatta right in their own classrooms, now they need to actually make it. They grapple with constructing stationary objects and backdrops to represent something dynamic and moving, i.e. a way of life. “How can we show how the gears, shafts, millstones, etc. work together to grind wheat when our windmill is painted on the wall?” “How do we teach about Lenape religion when their beliefs reached all areas of their lives and influenced everything they did?”

Work with a Purpose

The design and making process is working at a new integrative level. Earlier design/making experiences that were focused on developing the learner’s understanding of the problem now need to be aligned so that they are reinforcing this new narrative that will be shared with visitors to the museum. This creates a sense of purpose and agency to the work. It is not simply work that the teacher has asked them to do. It is work that will reach a broader audience and it is work that will be viewed critically by that audience. As such, the students understand that the stakes have been raised and this amplifies their commitment to the task at hand. They are working in the service of a clear purpose even if they are not clear on how best to complete the work. And it is this tension that pushes them forward to do their best work because the outcome (i.e., the museum visitor having a positive experience) matters to them.

Making that invites Meaning

For some students, it is not until this very focused making begins that key pieces of learning start to fall into place. The encounter with the materials and the design opportunities and challenges that they present help students to see how the ideas they have been exploring are interconnected. As the student works with cardboard to build an element in the Dutch settlement, he says, “Ahh, now I see why this is important.”

“Who is your character? What is your character doing and saying to teach about his or her life on Mannahatta?” This is the essence of the museum: the environment allows them to assume their character fully and put it into a greater context so that their teaching is from within. In New Amsterdam, Pheabe shows visitors why the garden behind her home is so important to her housework, while in the Lenape longhouse Bright Moon teaches important life lessons through storytelling around the firepit. Upon entering the museum, visitors, too, are immersed in the past. They move through the rooms, asking questions: not, “Can you tell me how the Lenape or Dutch lived?” but, “What are you doing? Why are you doing it like this?” Students are the experts because they have become their characters.

“Who is your character? What is your character doing and saying to teach about his or her life on Mannahatta?” This is the essence of the museum: the environment allows them to assume their character fully and put it into a greater context so that their teaching is from within. In New Amsterdam, Pheabe shows visitors why the garden behind her home is so important to her housework, while in the Lenape longhouse Bright Moon teaches important life lessons through storytelling around the firepit. Upon entering the museum, visitors, too, are immersed in the past. They move through the rooms, asking questions: not, “Can you tell me how the Lenape or Dutch lived?” but, “What are you doing? Why are you doing it like this?” Students are the experts because they have become their characters.

“What did you learn by making and doing the museum?” Our students reflect on their experience the next day. This metacognition gives them time to recognize the value of learning by making, contextualizing, and explaining:

“Gardening is in my head now, because as I was making it [the garden and gardening tools], it was like I was doing it, except they didn’t use paper and clay.”

“I felt like a Lenape. Once I became a Lenape, life was really hard.”

“I already knew about how they built longhouses, but after doing it and explaining it I learned how it’s real and how it’s really effective.”

“I learned about how to build snares from reading about it, but it’s like I got reborn into a Lenape village and learned it all over again!”

In the museum, students are not simply presenting what they know in a static way (imparting information); they are engaged in the iterative process of recreating their understandings.

In the museum, students are not simply presenting what they know in a static way (imparting information); they are engaged in the iterative process of recreating their understandings.

As they interact with visitors, they step out of what has become familiar territory to them, and see it from an outside perspective once again. The audience helps them see what they already know in a new way and the act of making creates a crucial context for this learning.

CREATING COEXISTENCE: Stepping into a Complex Society

“Little Fox, we have received a message from your Dutch friend, Antonius. Their Director-General, Willem Kieft, has declared that he plans to force us, Lenape, to pay a tax in exchange for the protection they claim to provide us.”

Little Fox and Antonius met one day while gathering oysters by the river and became friends, and have continued to meet from time to time. The Dutch and Lenape live on different ends of the island, and even though their trading relationship allows for occasional interactions, it is unusual to have personal friendships develop between the two peoples.

The Lenape villagers (Students-in-Role – see glossary) react to this urgent news: “This is not fair. They think that we signed a contract saying they could have some of our land, and in exchange they would help protect us. But we didn’t really sign a contract. We don’t believe in owning land. When that trade was made, we thought we were agreeing to all live together and help each other. And now they’re asking us to pay for that.”

The next day, they gather with their Sachem (Teacher-in-Role – see glossary) for a Council Meeting. In their democratic fashion, each person is given a chance to express his or her opinion about what to do about the tax. Their immediate response is to refuse to pay, but then some villagers express their concern that not paying it would ruin their trading relationship with the Dutch. As the Sachem listens to and summarizes the varying opinions, the group eventually arrives at the consensus to not pay the tax.

Meanwhile, a Dutch family in New Amsterdam is having a different conversation: “I just came from town. They’re saying that the Lenape won’t pay the tax! What’s that going to mean for the colony?” says Papa (Teacher-in-Role), as he enters the house. Antonius, upon hearing this, thinks about his friend, Little Fox. He shares his father’s fears about what will happen. He is thinking not only about how it will affect the colony, but also about how it will affect his relationship with his Lenape friend. As the conversation continues at the dinner table, he learns more about what this tax is about. His father explains how he is one of the advisors to Director-General Kieft and tells them that Kieft is considering war with the Lenape. He asks his family (Students-in-Role) what he should advise about the tax situation, even though Kieft has been known to do what he wants regardless of what his advisors or the colonists think. His family members share their concerns that war would hurt trade with the Lenape: “Isn’t that what we’re here for?” They also discuss how unfair it is that they, the colonists, are the ones who know what’s best for the colony, but that Kieft does not listen to them. “He’s going to ruin things for us!”

These two scenes are happening simultaneously in two different third grade classrooms. In this part of our study, we play out the Mannahatta story through the interactions of the Lenape and the Dutch colonists, and how these interactions are complicated by historical events that unfold. These experiences are seen through the eyes of children — a Lenape and a Dutch child — who become friends. One class is the Lenape village and the other is Dutch New Amsterdam. Their homes are the environments they created in their respective classrooms for the Mannahatta Museum. Like one’s own home, the Lenape longhouse or Dutch home grounds them in one perspective, and when they meet their friend in the other room, they are learning about the other culture.

Why the Other Matters

Here again, we see the crucial role that empathy plays in this work. Moreover, in this phase of the work the need for empathy is also tied to the challenges posed by the relationships that drive the students’ experiences. The student-as-designer seeks to understand the other, but cannot remain separate from the other. Both have a stake in the encounter and its outcome. This helps to reinforce the idea that good design, making and problem finding and solving is about understanding human needs (i.e., before you make something you really need to understand the needs of the user and it is better to make with the other than only for the other). Students begin to realize that their ideas live in a social context and often there are important tensions between ideas that must be uncovered and respected. They also begin to understand that good design seeks to turn these tensions into opportunities for positive change.

This “coexistence” framework allows students to live out the interactions and problems that arise within a dynamic and diverse society. They grapple with complex problems that have been universal human questions throughout time: How do you co-exist peacefully? How do you share space and resources? How do you work out competing interests? What do you do when you reach the limitations of your relationship? Whose fault is it? How do you deal with the other, the unfamiliar?

How do our students navigate these diverse views within their roles? Do they decide which view is “better”? No, they do this by being curious, by befriending.

Now that each class has experienced the fallout of Kieft’s tax from their respective points of view, the friends eagerly find each other to discuss the recent events and compare their perspectives. The moments of interaction between the two friends provide opportunities for students to share the different points of view and teach each other more about Lenape or Dutch culture. For instance, in this series of lessons, the goal is for students to learn about varying perspectives on Kieft’s Tax, and to gain an understanding of the decision making process (i.e. government) in Lenape and Dutch societies.

We intentionally want the students to be children — not adults — in this drama to maintain an open stance as they learn about each other, rather than having them re-enact the partisan politics of the time. However, by taking on the role of children, students are in some ways a witness to events that are driven by the adults around them. They are not the Director-Generals or Lenape chiefs solving the problems, but they have to think about how they can still have a voice within this society. They are the Lenape community members who participate in a democratic meeting or Dutch colonists petitioning against their leader. Is that enough? We don’t think so. In our curriculum, we want to them to be agents of change — without having to change history.

Designing for Social Innovation

It is in the context of these interactions that students begin to see the design and making activities they have been engaged in as having a broader purpose. The orientation to question finding and problem solving begins to shed light on the possibilities for design and making as tools for addressing pressing social justice challenges and the value to be derived from engaging in social innovation work. This focus will move to the forefront in the final future facing phase of the project. It also sets the stage for looking at entrepreneurship through the lens of social innovation, which focuses attention on ideas and processes that create social value as opposed to individual gain. This orientation is also well aligned with core values of the school’s mission.

We return to our drama: (Narration – see glossary) “Willem Kieft’s tax resulted in a war between the Dutch and Native Americans in the area that lasted two years (1643-1645) and resulted in extensive destruction to both Native American villages on and around Mannahatta and the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam.” Dutch and Lenape parents (Teacher-in-Role) tell their child, “Even though the war is over, you can’t see each other; it’s too dangerous.” (Narration) “The children went to bed feeling sad, but woke up knowing that they could solve the problem. They just needed to see their friend.” The pairs get together to talk about what would need to happen for them to remain friends (i.e. for the Dutch and Lenape to co-exist peacefully on Mannahatta).

We return to our drama: (Narration – see glossary) “Willem Kieft’s tax resulted in a war between the Dutch and Native Americans in the area that lasted two years (1643-1645) and resulted in extensive destruction to both Native American villages on and around Mannahatta and the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam.” Dutch and Lenape parents (Teacher-in-Role) tell their child, “Even though the war is over, you can’t see each other; it’s too dangerous.” (Narration) “The children went to bed feeling sad, but woke up knowing that they could solve the problem. They just needed to see their friend.” The pairs get together to talk about what would need to happen for them to remain friends (i.e. for the Dutch and Lenape to co-exist peacefully on Mannahatta). Through this “imagined-but-real” friendship, third graders are thinking about the big ideas of what makes a community work. In trying to save their friendship they identify what a complex and multicultural society needs for survival: a way to share land and resources fairly; a strong leader who allows the people to have a voice; acknowledgement of each other’s differences and needs. In their design for Mannahatta, equity and respect are the essence of a successful society.

CREATING THE FUTURE: Becoming Agents of Change

“New York City is in a state of emergency, and the situation is grim.”

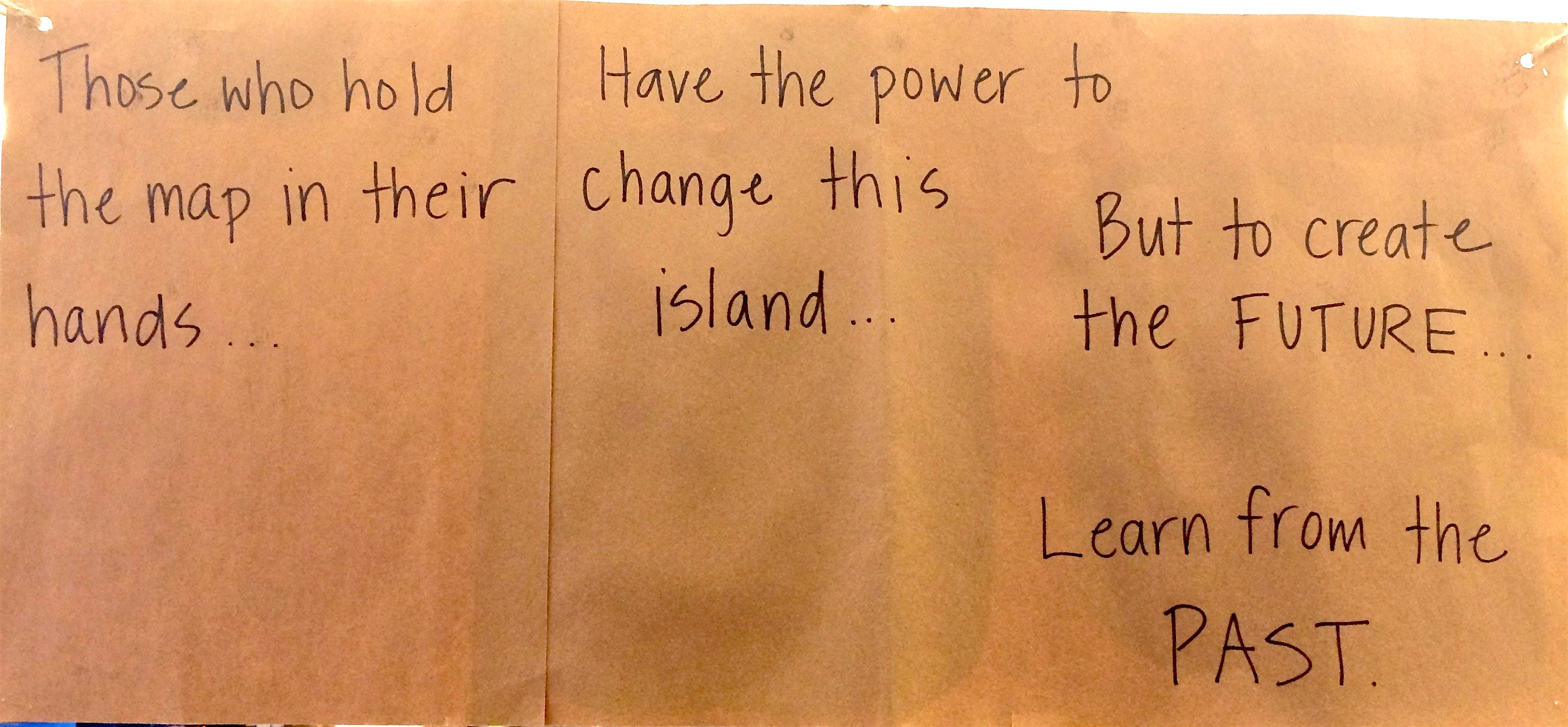

After many months of living in the past, Team X discovers their true mission: to save the future of New York City. Now the call to action they received at the beginning of the year makes sense: they must use what they have learned about the past in order to create the future.

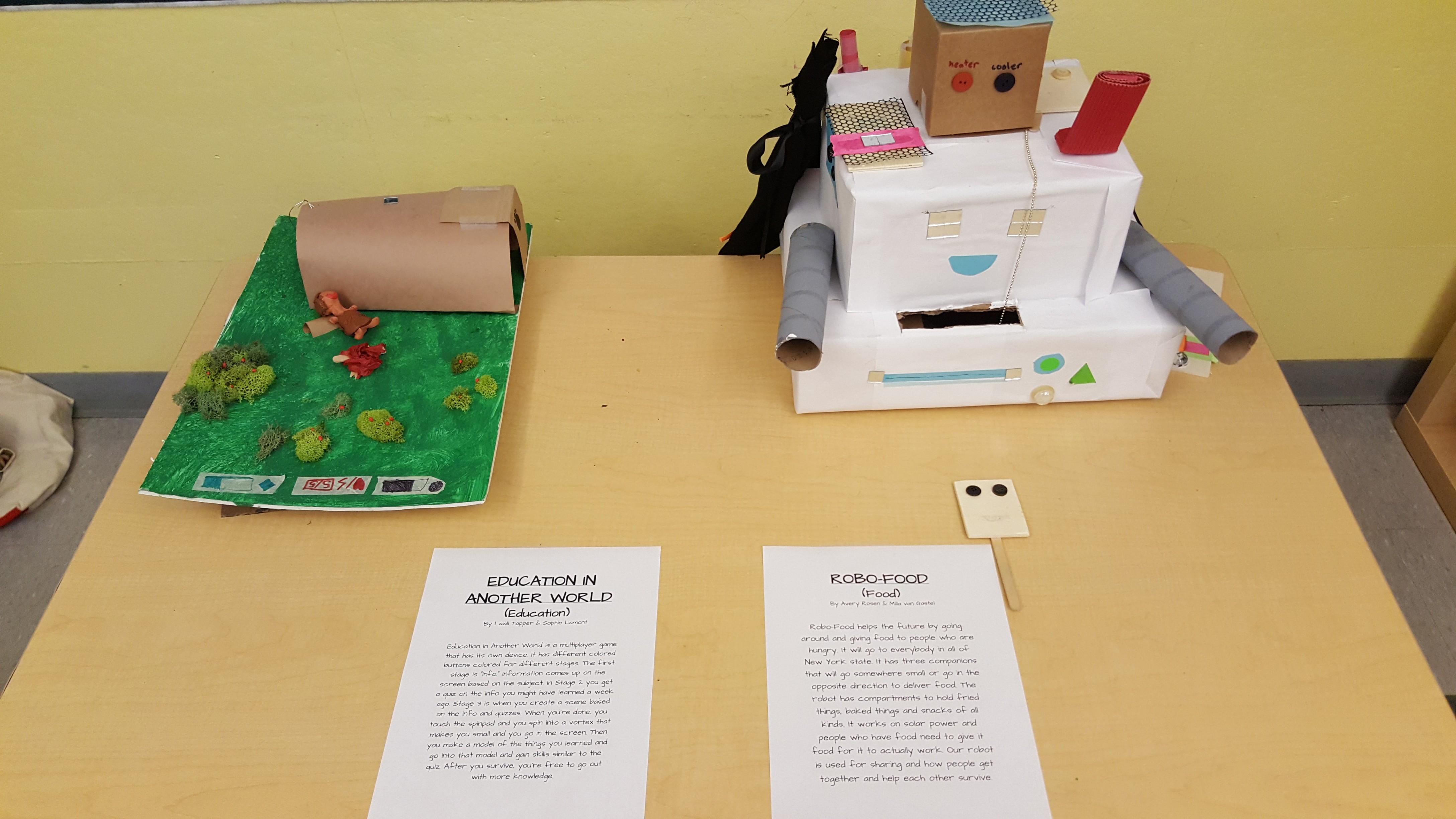

In a way, they have been creating all along, but this time it is different. Whereas students were taking apart and putting back together existing systems, now they must come up with a whole new design. In making the City of the Future (see Note 2), students are thinking like urban planners, innovators, and entrepreneurs. They dream the impossible.

Designing for Voice/Agency

Throughout the process, students have been asked to think about how they design for a variety of external audiences and for themselves. In addition, within the context of the drama that serves as the frame for their experience, they are able to see that every character, independent of role or status has voice. Within the context of their historical inquiry, the goal here is understanding and empathy not the fanciful creation of a “new” history. Exploration of “what might have been” is important, but at this moment connecting to a deeper understanding of how the history unfolded is important. It also helps them to understand that the history that we’ve inherited is not without dissenting views even though these views may not be as clearly represented in the formal historic record. At the same time, their desire to make history (the “what might be”) will be addressed in the final phase of the project.

We place no limits on their creativity. The only criteria is that their inventions are purposeful, that they use past practices as a guide, and that they consider all of the parts that make up a successful society.

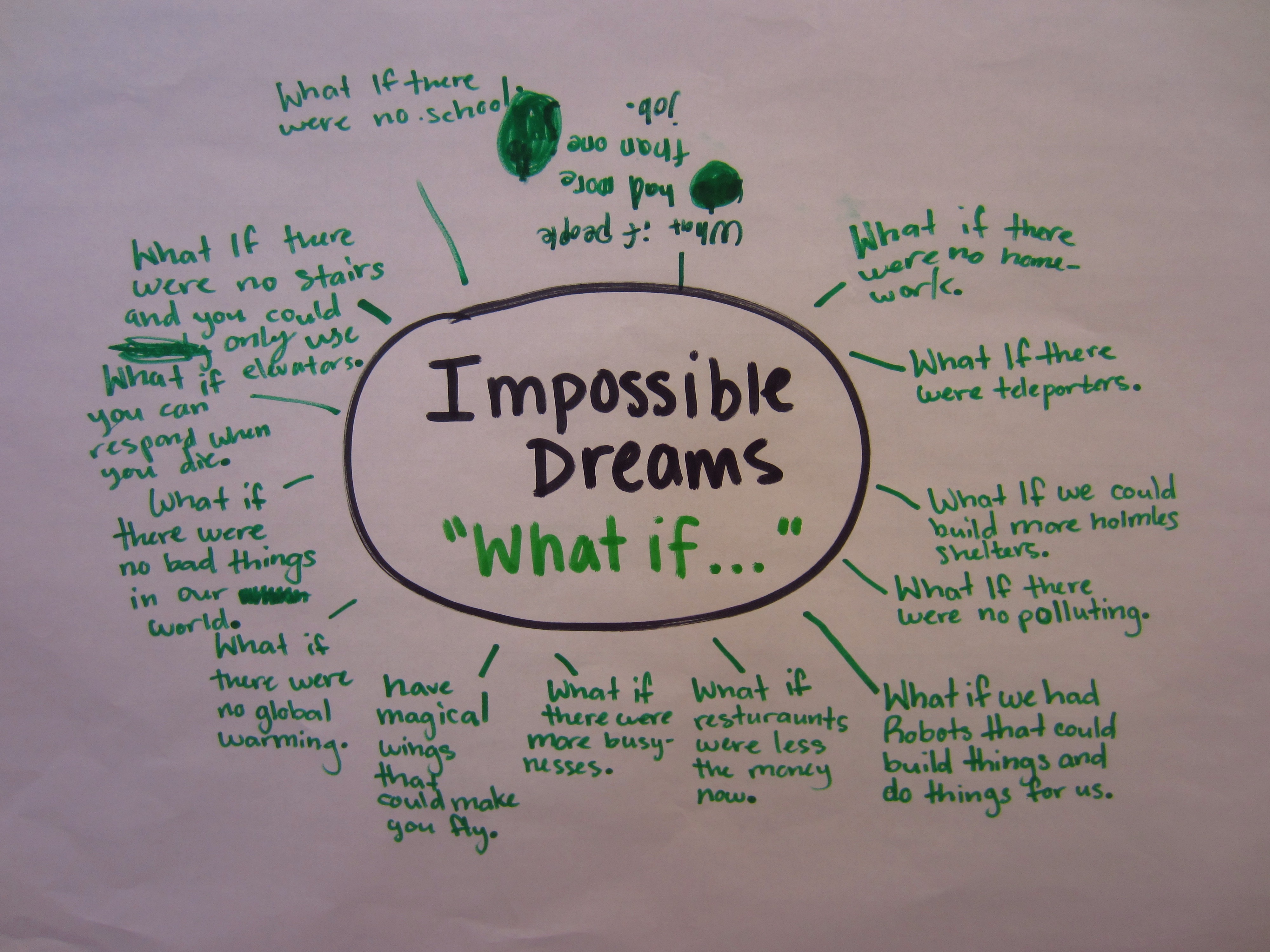

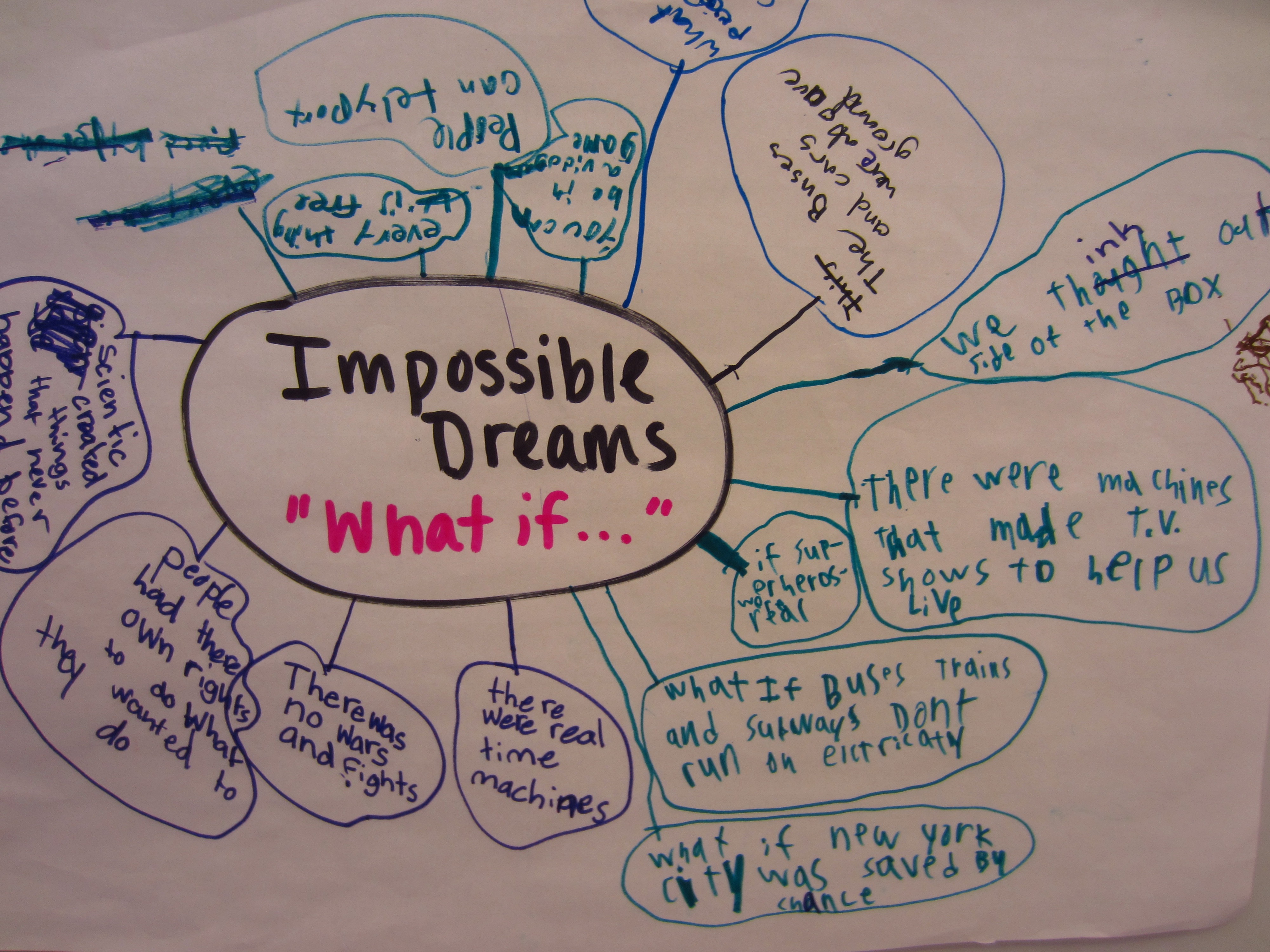

“What if we could breathe underwater?”

“What if there was no money?

“What if everyone trusted each other so we didn’t need any rules?”

“What if there was a park next to every building?”

Students organically build on to each others’ ideas and are taught to say, “Yes, and…” instead of “No, because…” They brainstorm and troubleshoot together and learn that this is a group process in which everyone has ownership in every idea that is generated. As they develop their ideas, they are invited to bring their designs back to the group for feedback: their classmates help them work through limitations that they bump up against as they turn a general idea into a complex system. “We have a food machine that distributes food to people who need it, but we’re not sure where the food comes from.” Their peers offer possible solutions: “What if solar panels could create energy that turned into food?”, “What if everyone who has enough food gives their extra food to the machine?”, “What if restaurants and farms gave some of what they made to the machine?” Students return to their plans to refine and expand them. The subsequent revisions contain ideas from the whole class.

Their project designs are blueprints for a sustainable city. Eventually each group pitches their best ideas to the class, who then votes on one project per category: housing, food, transportation, education, government, religion, community life, natural environment, jobs/work, and games/entertainment. They then begin working on their prototypes.

Their ideas are wildly utopian; they are not constrained by real world barriers. But this doesn’t matter — the point at this moment is not to come up with realistic solutions to save the city, but to think like an innovator and an agent of social change. Beyond just making models for a final presentation, they are prototyping a way of thinking that could be used to solve problems in the future: Pay attention. Learn from the past. Don’t give up. Make something that is different and better than what already exists. Their Team X mission to save New York City may not be real, but their sense of agency is. They know they can change the future for real.

An Entrepreneurial Mindset

The final phase of the project calls on students to work through the design thinking process and builds on their prior inquiry. In this instance, students move beyond exploring the past and are tasked with finding meaningful questions about the future and working towards solutions. This inquiry supports the development of an entrepreneurial mindset in that students are thinking and doing in a space that they have not explored before. Additionally, this work is carried out in order to achieve a desirable outcome. To do this, students working individually and then in teams must first assess the situation. This allows them to better understand the wants and needs of those for whom they are designing and the resources that are available to them. They design alternatives; some of which are wholly novel in their approach while others see new opportunity through the combination of existing solutions. Whatever the pathway, they are motivated by the idea that what they design will lead to something better that adds value. In the context of this work they learn how to advocate for their ideas and how to collaborate in the service of a shared goal.

Afterword

And so we return to the idea of the curriculum as prototype. While the design of our third grade curriculum will continue to evolve as students and teachers work and learn together, it will do so in the context of a series of scaffolded lower, middle and high school experiences. These curricular iterations also leverage and extend the design, making and entrepreneurial skills that were essential to our third graders’ experience. In so doing, our students’ inquiry into the past will not only inform their present, but will inform their future as well.

GLOSSARY

Definitions adapted from http://www.imaginative-inquiry.co.uk and https://tesoldrama.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/process-drama-conventions.pdf

Imaginative Inquiry

A teaching/learning approach that brings together three pedagogic strategies: community of inquiry, drama for learning, and mantle of the expert. Exciting and meaningful contexts for learning are used to engage students in challenging and purposeful curriculum activities.

Inquiry Learning

The curriculum is seen as something to explore rather than deliver, and children are active agents in this process. Students and teachers work together to acquire, apply, and develop new knowledge, skills, and understanding.

Drama for Learning

Using the conventions of theater (point of view, tension, and narrative), students and teachers work together to invent imaginary scenarios that give meaning and purpose to curriculum study. It is not a performance, and does not require acting. It is a role-play game where participants make up the rules and invent the moves.

Process Drama Conventions:

- Teacher/Student-in-Role: The teacher manages the learning possibilities and opportunities provided by the dramatic context from within the drama by adopting a suitable role in order to achieve such results as exciting interest, controlling the action, inviting involvement, creating tension, challenging superficial thinking, or developing narrative. Students-in-Role signifies students who are enrolled as specific characters in the narrative.

- Narration: The narrator sets the scene, signals a transition and/or directs the characters’ actions in a narrative “overlay” while students-in-role move through the story silently (pantomime). The narration may give directions, additional information, or comment on the action of the scene or the motivations of characters.

- Rituals: Stylised enactment bound by traditional rules and codes, usually repetitious and requiring individuals to submit to a group culture. Words and actions for repeated rituals in the scene. (Example: Students use a ritualized chant or phrase to mark the beginning and ending of a “time-travel” experience.)

Mantle of the Expert

The class adopts an expert point of view within an imaginary scenario. A problem or task is established and the teacher/students use imagination to explore it. The teacher guides the drama, stepping in and out of a role as necessary, providing encouragement and motivation to the experts.

Time Travel

Using the principles of improvisation our students “time travel” to the past. In the beginning of the year, our students design and build their own version of a time machine in their woodshop class. The creation of a physical object that they have designed gives them a sense of personal connection to their journey into the past. The physical “time machine” also helps students to bridge the divide between the concrete and the abstract by creating a developmentally meaningful symbol to help mediate their journey through time. We use a ritualized chant or phrase to mark the beginning and end of each time travel session. Rather than providing our students with a script, the time travel experience signals them to use a particular mindset to look at and interact within history. Although we ask them to envision themselves as people from the past, they are actually using their own authentic feelings, experiences, and knowledge to engage with history. Unlike performing in a play, when actors have to entirely assume a role that is not themselves, during improvisation, participants bring a sense of self-awareness while still trying to imagine how someone else would behave or respond within a given context. In this case, the context given is a problem that a group of people may have faced in a certain time and place from the past.

NOTES

All quotes from Agnes De Lima are from the book The Little Red School House.

Lima, Agnes De. The Little Red School House. New York: Macmillan, 1942. Print.

Note 1:

- Mystery Time & Place Artifacts (Amsterdam, 1600s)

In addition to a variety of physical objects (e.g., Dutch bonnet and spindle), students also explore a number of primary source print materials:

Additional “artifacts” like the two examples below help to frame students’ inquiry around the “experience” of those who lived in the past. In this way, students come to see the narrative dimension of their journey to and investigation of the past.

Drama: Merchant Comes Home to Family

Time machine set by X (unknown time/place)

FATHER:

- “Come, children, look at what I brought home!” — show beaver skin, ask if they know what it is

- “This was brought back from a far away place across the Atlantic Ocean! Not many people from Europe have been there — only a few brave explorers — men who sail to unknown places all over the world to see what’s there — have been there. Henry Hudson is one of those explorers, and his ship just got back a couple of days ago, and news has been traveling fast. They say that this place is covered with forests, with plenty of wild animals living in it—beavers, muskrats, otter, mink, raccoon, rabbit, deer… And there are people living there too, who are very different from us.”

- “Do you know what this [point to fur] means for us? The hats that I make in my shop are made from this fur. But over the years, it’s been harder and more expensive to get beaver fur. The land that we have been clearing to build farms and cities over the years has destroyed the beavers’ habitats, and so they have been disappearing.”

- “These beaver fur hats are so popular now — if you own one of these hats, it’s a sign that you are rich and important, and so, naturally, everyone wants one. My business would be booming if I had more fur to make more hats. If it’s true that there are beavers all over this new world across the ocean, imagine how much business I could do! Imagine how rich our family would become…why, I could pass the business on to you, or you [pointing to students]!”

- “This is a new time — not like before, when we only had what we could make or grow here at home. Now, there are ships coming and going, bringing back goods from places all over the world — China, India, Africa… My hats could be shipped to all these places to sell!

From the Journals of Henry Hudson:

January, 1609

I have just been named captain of the ship, “The Half Moon”! I signed a contract with Dutch business merchants who want me to find a new route to China and India so that they can trade goods more easily. This will be my third voyage in search of a shorter and faster way to get to Asia. Even though my first two voyages were unsuccessful, and we had to turn back after months of sailing and searching, I am certain that this time I can find a way to Asia by sailing across the Atlantic Ocean.

If I am successful, it will bring me fame and fortune. Not only will it bring more business to the Dutch merchants, but I will be able to trade goods too. More importantly, I will be known as the explorer who found a way to Asia that no one knew about and that no one believed was possible.

September, 1609

We have reached the land that is across the ocean, and while we have not yet found the opening that will lead us to the Pacific Ocean and to Asia, we will rest here and few days, replenish our resources, and hopefully trade goods with the natives who live here.

I sailed to the shore in one of their canoes with an old man, who was the chief of the tribe consisting of 40 men and 17 women; these I saw in a well constructed house of oak bark and circular in shape.

The land is the finest for cultivation that I ever in my life set foot upon, and it also abounds in trees of every description. The natives are a very good people.

Their food is maize or Indian corn which they cook by baking and it is excellent eating. They all came round the ship, one after another, in their canoes, which are made of a single hollowed tree; their weapons are bows and arrows, pointed with sharp stones, which they fasten with hard resin. They had no houses but slept under the blue heavens.

Note 2:

Using Imaginative Inquiry to teach about the past was first introduced to Elaine by progressive educator and Imaginative Inquiry consultant, Kelli Dawn Holsopple, as part of the Phoenix Theater’s In-Flight artist-in-residency program at the East Village Community School (EVCS) in New York City. The “Secret Time-Traveling Archaeologist Mantle”(see Thinking Like Social Scientists) of the entire class becoming enrolled as a secret “Team X” was first piloted in a third grade class in 2009, with subsequent iterations implemented in grades 2-4 at EVCS, and then at the Little Red School House (LREI), starting in 2012.

The concept of “becoming” the team through application letters and tests, including the “Riddle” to learn from the past to create the future was part of the mantle devised and initially implemented by Kelli, and has served as a framework to drive and give purpose to the third grade curricular study of early New York history. The “Emergency” lesson (see Creating The Future), in which the high stakes problem of the city needing a plan for the future to save the plants, animals and people, in the form of an emergency news report, was scripted and originally filmed by Kelli, thus leading to the creation of the City of the Future projects.

We are grateful for the ingenious work and ongoing inspiration Kelli has bestowed upon our craft, as teachers of history, social justice, and young, powerful minds.

For more on Kelli Dawn Holsopple’s work, see:

http://blog.communityworksinstitute.org/2016/04/29/ecstatic-learning-an-invitation/

Note 3:

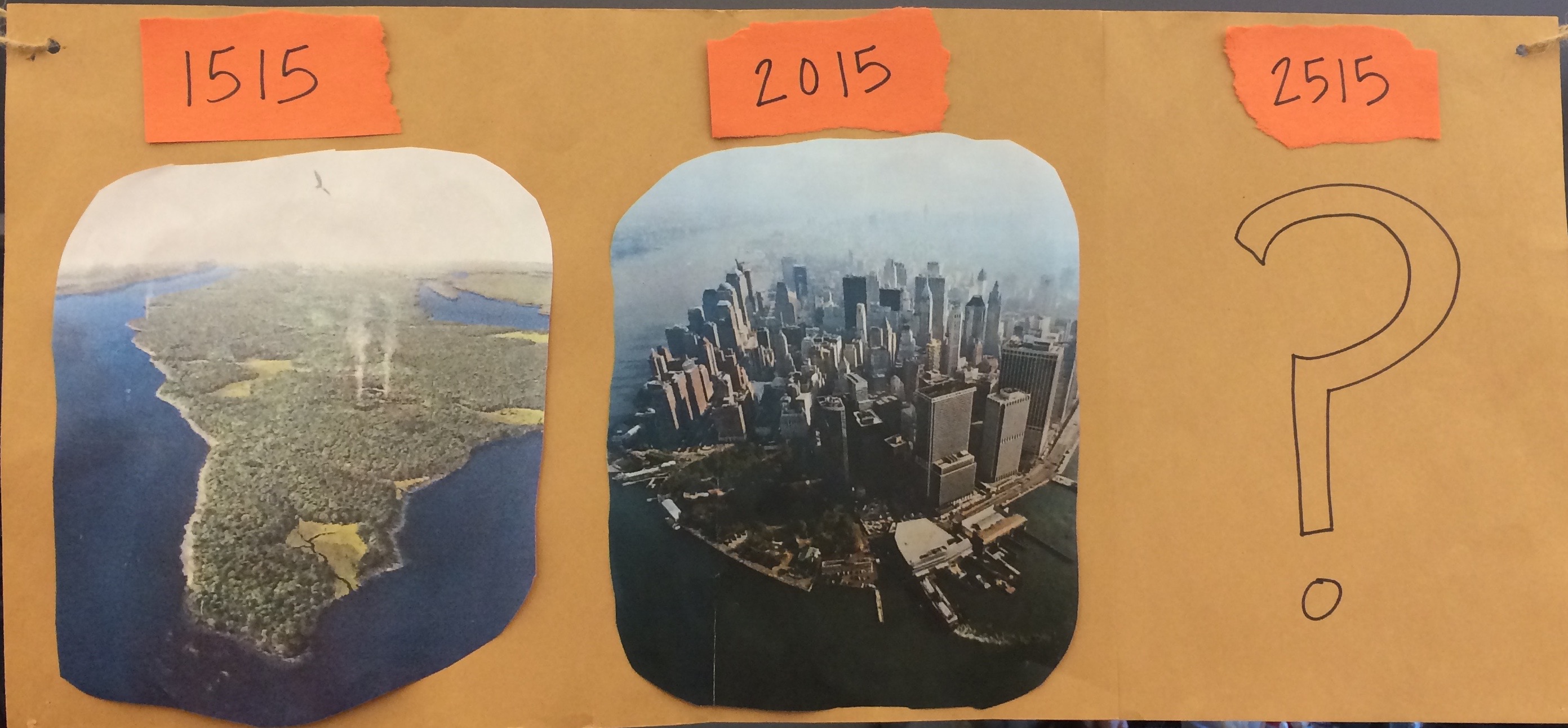

The idea of connecting the three time periods of New York City history — 1515, 2015, and into the future — was inspired by Eric Sanderson’s research and ideas in the book, Mannahatta (Abrams, Inc., 2009), in which Sanderson, a Senior Conservation Ecologist at the Wildlife Conservation Center in New York, explores Manhattan’s geography and biodiversity in 1609, 2009, and posits a vision for the year 2409. For more information, visit the Mannahatta Project website: https://welikia.org

Note 4:

We recognize there may be some question about what it means to have students “dress up like” or “act like” Native Americans. Our goal is to set up contexts and problems in which our students can imagine and learn about life as a Lenape, without them thinking they really are Lenape or acting like them in a stereotypical way. This is why we present the learning experiences within a process drama framework, where students know that they are actually themselves: we tell them that they should imagine what it would be like as Lenape in that situation, but that they are going to respond using their own feelings and experiences. This “acting like a Lenape” is really an exploration of a problem within a historical context. Our students do not try to pretend to speak like someone who doesn’t speak English or use an accent; we recognize that the Lenape did not speak English, but that we are speaking it in order to understand each other. They also do not dress up in costumes, but instead rely on their imaginations to visualize the experience (for example, they can imagine they are using a spear for fishing). On occasion, we (the teachers) use a small prop to mark a shift between characters. These items are meant as a symbolic tool, not an imitative costume. Not only does the process of teaching through drama not require dressing up anyway, but we are also recognizing a cultural sensitivity.