Revisiting Founding Principles

Since its founding, learning, growth, and a capacity for navigating change have been at the center of the LREI experience. For LREI founder Elisabeth Irwin, this forward-looking orientation was grounded both in a deep respect for children and for communities that learn together, and in a set of guiding progressive principles. As an experimental school, the goal was not simply to be different or to pursue change for change’s sake, but rather to engage thoughtfully with the world and with each other in the service of growth and progress. As Irwin observed:

The school will not always be just what it is now, but we hope it will always be a place where ideas can grow, where heresy will be looked upon as possible truth, and where prejudice will dwindle from lack of room to grow. We hope it will be a place where freedom will lead to judgment—where ideals, year after year, are outgrown like last season’s coat for larger ones to take their places.

We thought that it would be interesting to highlight three of these foundational principles and explore how students and teachers in our current program experience them. We will examine how a deep understanding of the whole child and the value of the school-family partnership is at the center of the Lower School Home Visits program, which is an important part of the Fours curriculum. In the Middle School, we connect the school’s longstanding commitment to integrated curricula and project-based work to this year’s pilot of “Big Time,” which created extended half-day long blocks for learning. Finally, we report on the inaugural High School Eleventh Grade Trip, which focused on the challenges and opportunities faced by our nation’s cities and sent teams of students and faculty to six locations. This trip affirmed the value of the school’s original activity curriculum, which pioneered the use of field trips to narrow the distance between the classroom and the world, and the essential value of student-centered and student-led experience. These three examples, along with most other aspects of the LREI program, are aligned with the foundational idea expressed by Agnes De Lima in the 1942 book The Little Red School House that:

We thought that it would be interesting to highlight three of these foundational principles and explore how students and teachers in our current program experience them. We will examine how a deep understanding of the whole child and the value of the school-family partnership is at the center of the Lower School Home Visits program, which is an important part of the Fours curriculum. In the Middle School, we connect the school’s longstanding commitment to integrated curricula and project-based work to this year’s pilot of “Big Time,” which created extended half-day long blocks for learning. Finally, we report on the inaugural High School Eleventh Grade Trip, which focused on the challenges and opportunities faced by our nation’s cities and sent teams of students and faculty to six locations. This trip affirmed the value of the school’s original activity curriculum, which pioneered the use of field trips to narrow the distance between the classroom and the world, and the essential value of student-centered and student-led experience. These three examples, along with most other aspects of the LREI program, are aligned with the foundational idea expressed by Agnes De Lima in the 1942 book The Little Red School House that:

the general education aim . . . will be achieved, not through a routine process of instruction, but through a series of experiences, which will awaken the interest in the children and develop a facility for meeting individual and social situations… We believed in the beginning as we still do that children can be happy in school, that education must be thought of in terms of growth and comes by experiencing rather than by mere learning, and that life does not begin when school ends but rather, as John Dewey says, that “school is life.” (pp. 3 and 5)

The Fours Home Visits Program

A 1913 New York Times article about Elisabeth Irwin describes how she, “went to the homes of many children and, through her presence and counsel, brought about between parents and school authorities a better mutual understanding with regard to the needs and natures of individual pupils.”

And as Agnes De Lima writes:

Our teachers often visit their children’s homes and thus establish a warm and intimate relationship with them. A feeling of trust and confidence grows up. Parents know not only how their own children are getting on in school but how other children of the same age progress. The teacher also becomes aware of the special conditions which are affecting the child at home; where there are problems she is often asked to lend a hand in solving them. (p. 9)

The cultivation of these important relationships with families is still a hallmark of the LREI experience, but the concept of home visits has been expanded to include the students themselves in the process. In this way, the idea of building connections with families is married both to the practice of field trips, which was another learning method pioneered by Irwin and her colleagues, and a student-centered/led experience.

The cultivation of these important relationships with families is still a hallmark of the LREI experience, but the concept of home visits has been expanded to include the students themselves in the process. In this way, the idea of building connections with families is married both to the practice of field trips, which was another learning method pioneered by Irwin and her colleagues, and a student-centered/led experience.

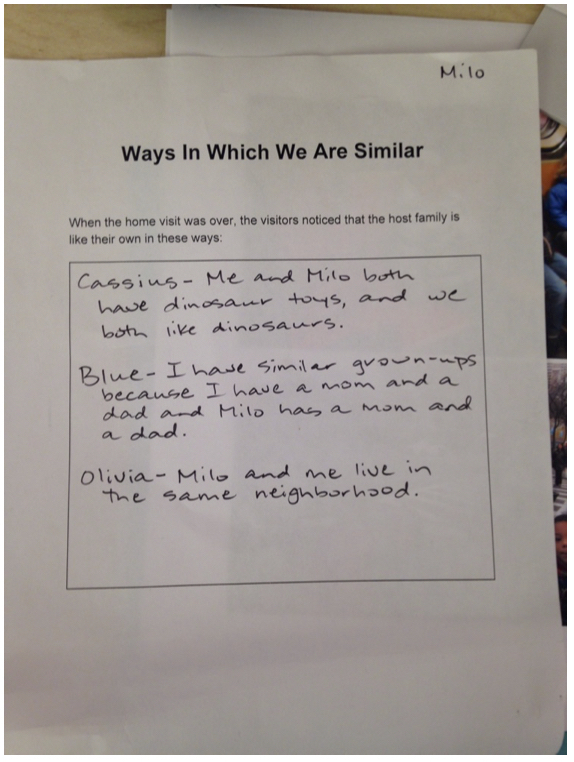

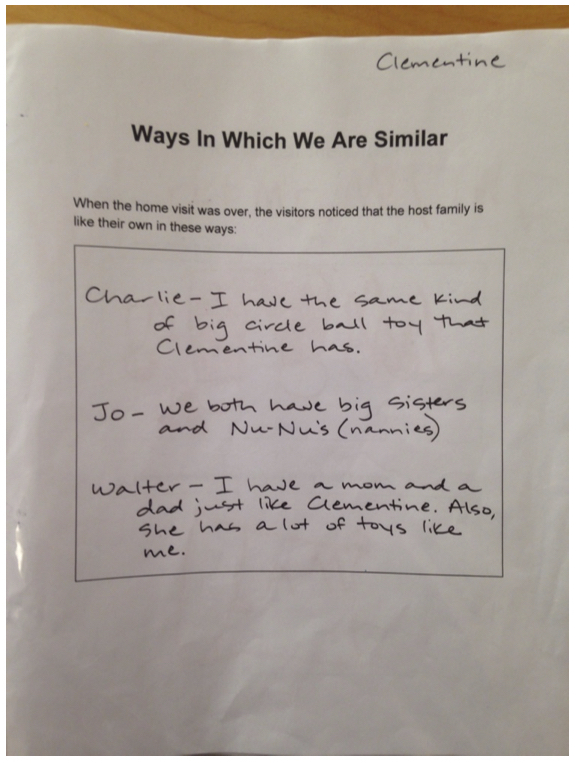

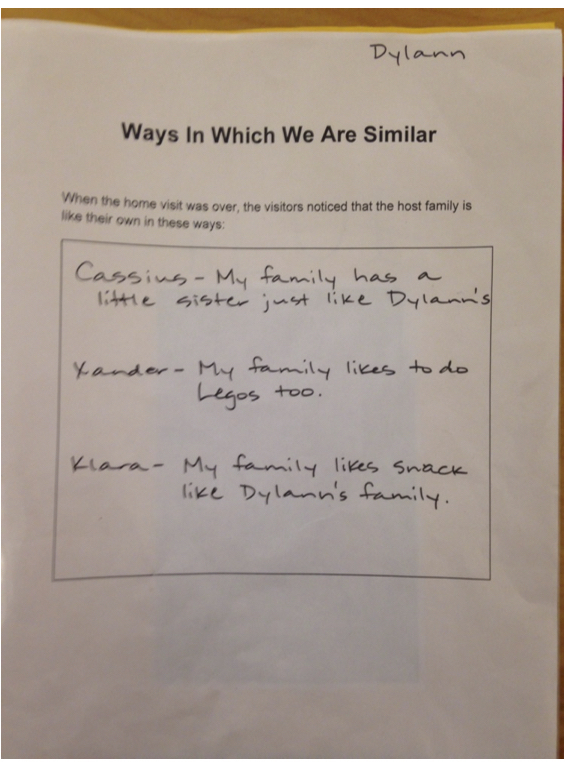

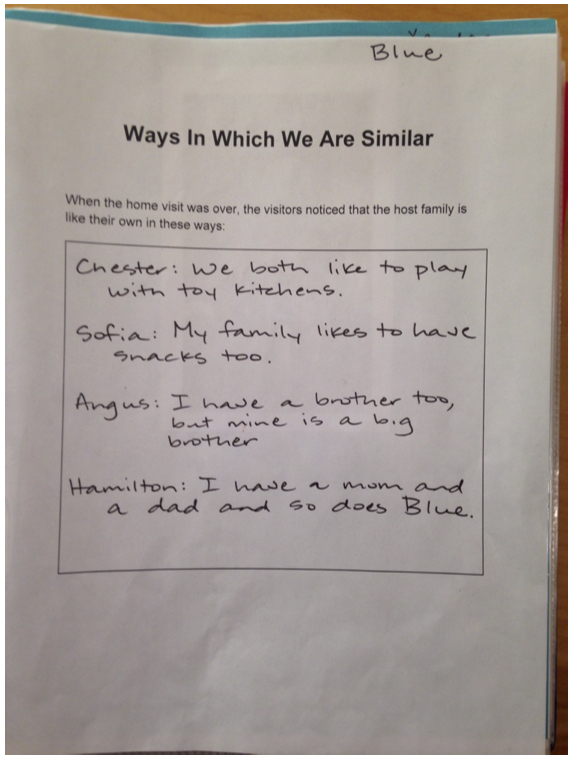

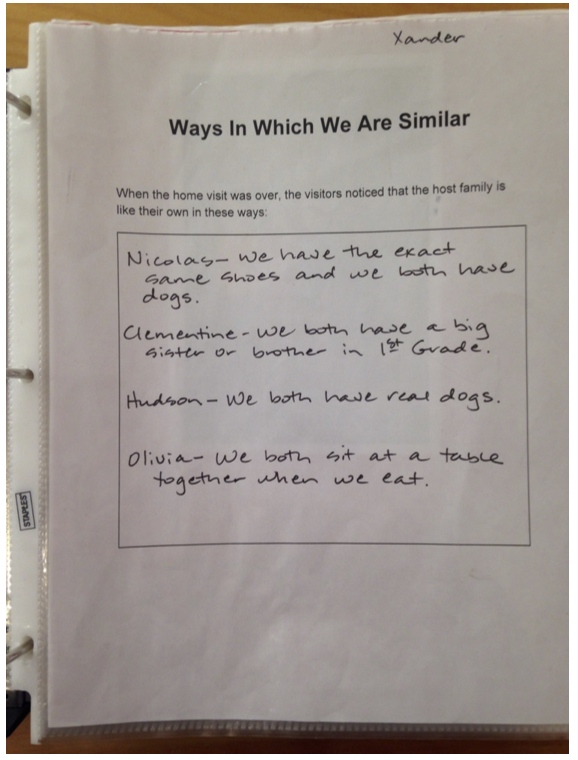

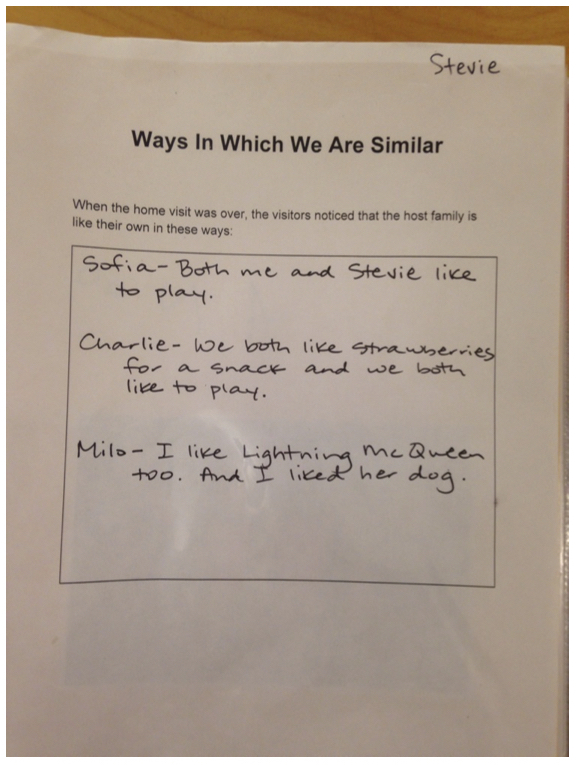

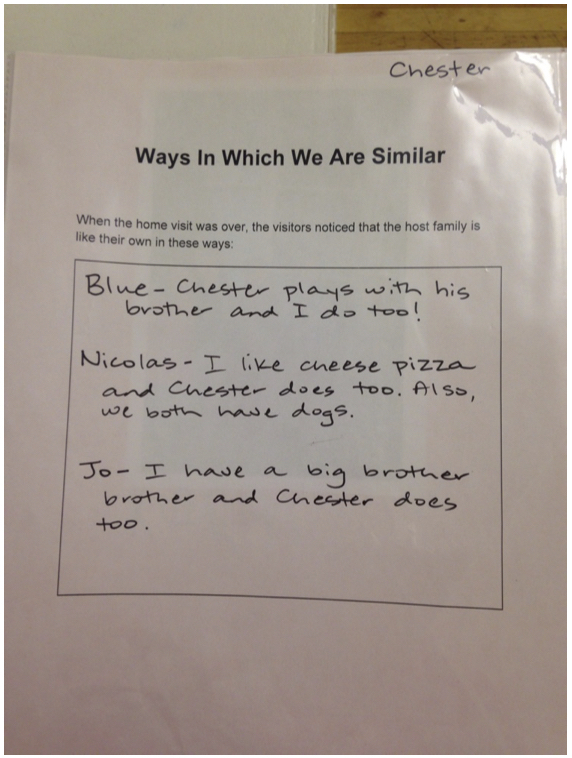

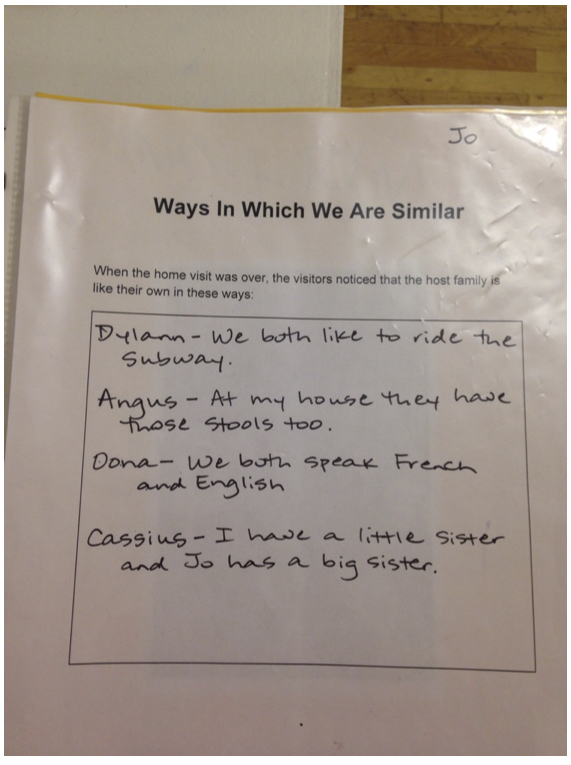

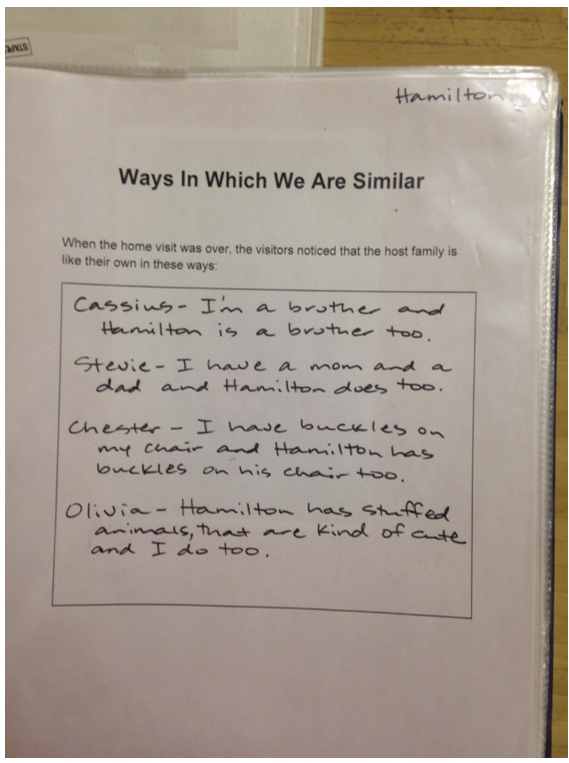

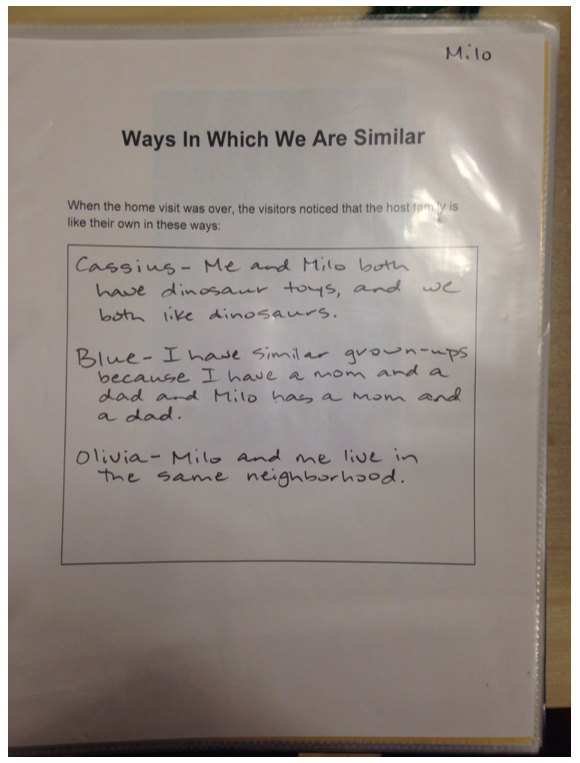

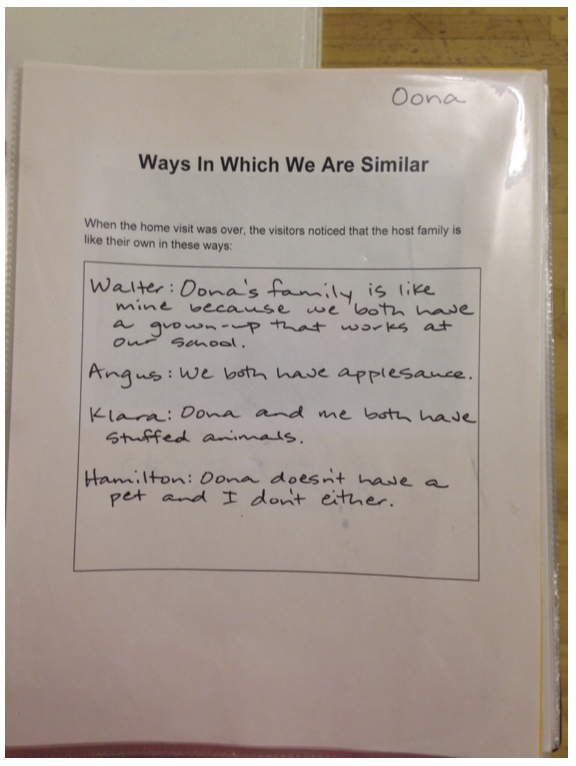

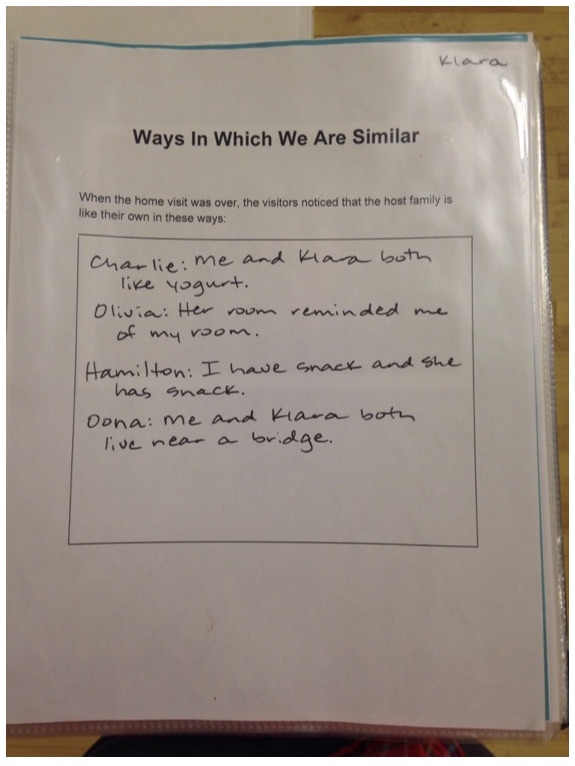

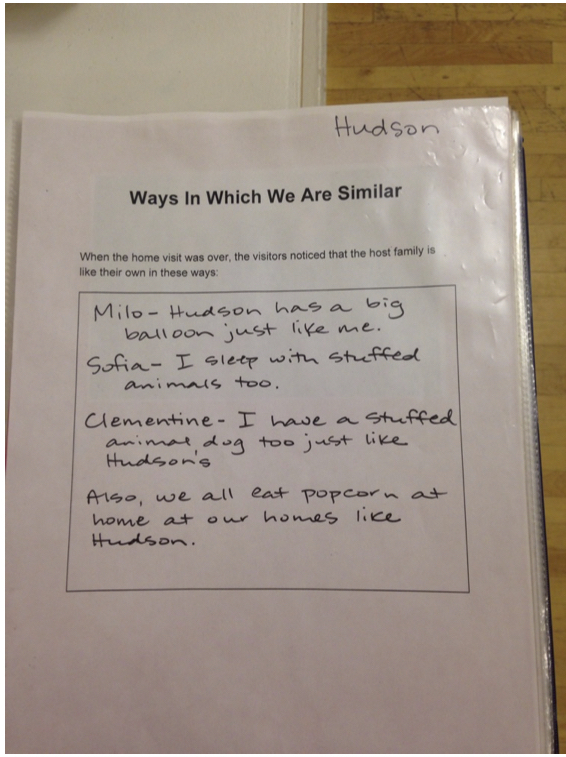

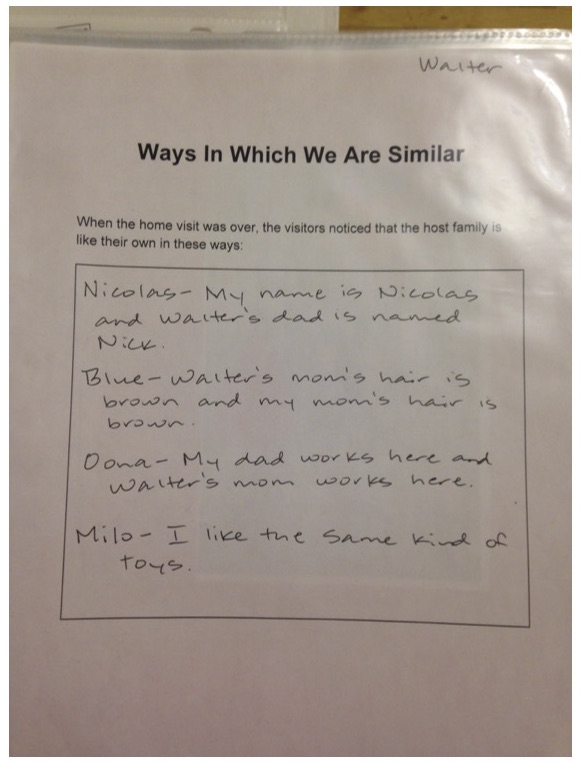

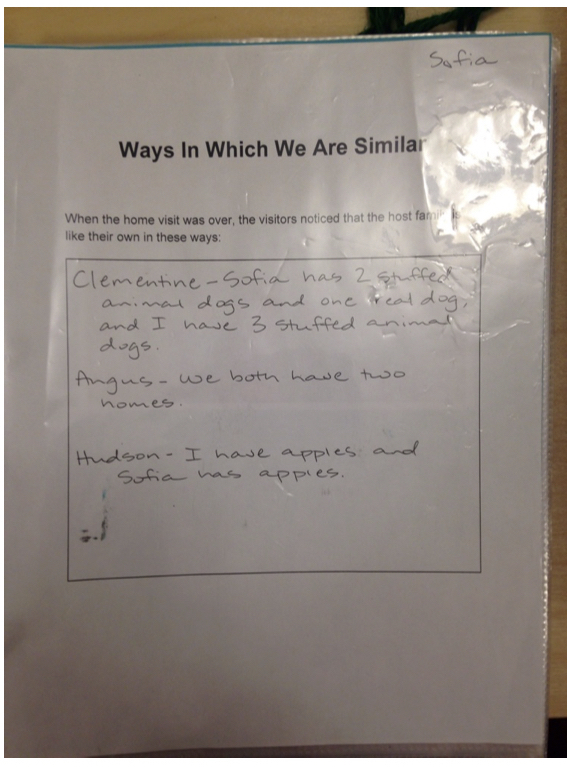

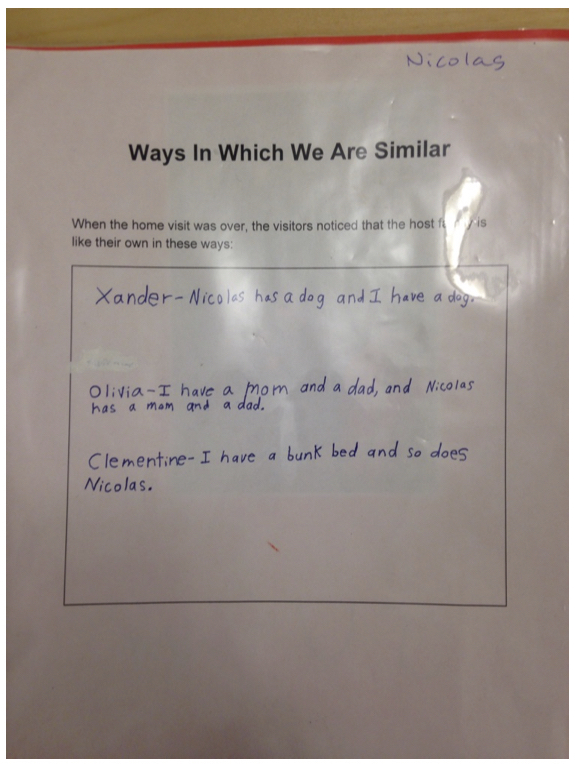

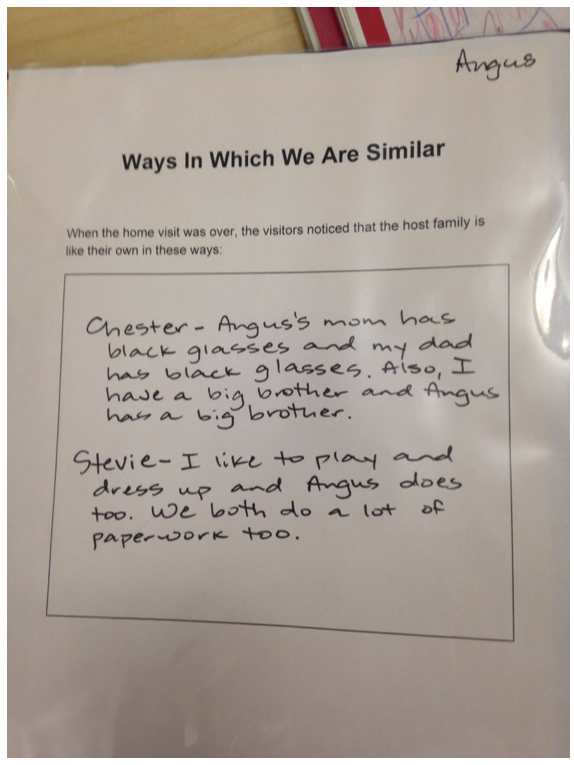

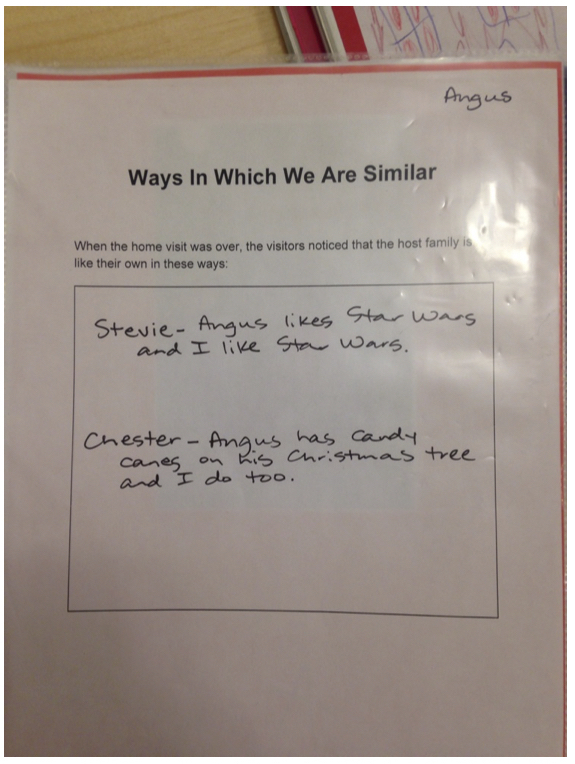

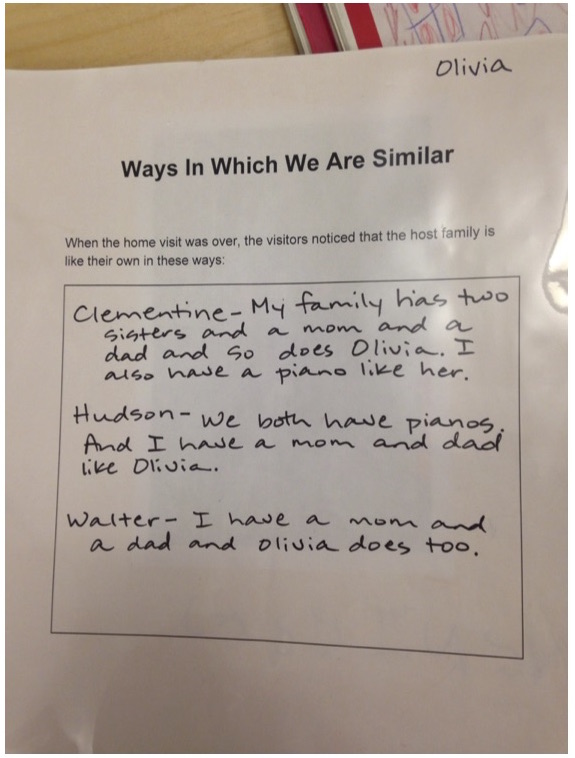

Beginning in November and continuing over the course of several weeks as part of the Family Study unit, each member of the Fours classes leads a field trip to visit their neighborhood and home. For these visits, small groups (five to six children) take trips to each other’s homes during the school day. These are not playdates, but rather a chance for children to learn about and appreciate the different families and home lives found in our community. While the home visits offer a unique opportunity for each child to feel valued, they also illustrate the commonalities in our families (they love and care for each other) and the differences (families can have different grown-ups and children, and eat different foods). With support and planning from their teacher, each child prepares to be a host and guide. Children show their classmates special parts of their neighborhood and the meaningful aspects of their home.

As Fours teacher Beth Binnard observes:

The host child shows the other children how to get to the home (teachers know of course) and what are the important aspects to their life at home (sometimes it’s a toothbrush, sometimes a stuffed animal, sometimes a book or toy). It’s very powerful to see a child in this light, and it’s equally powerful for the other students to see the host child in this way, even if they can’t fully articulate this insight.

While on the visit, students spend time drawing pictures of things they notice and gather information about elements common to each visit (mode of transportation, floor number, neighborhood in the city, etc.). This work continues back in the classroom as the children discuss observations, share pictures, analyze data and write about significant aspects of their visits.

These visits are meaningful to both children and adults. They affirm the idea that when children are able to share aspects of their home life with classmates, the experience itself generates opportunities for deeper learning and understanding. The Home Visits also play a huge role in connecting the children as a community of learners. A child with separated parents goes on a home visit to another child with separated parents. Each student visits a home in a different borough at least once as well as different neighborhoods from their own. Children also compare and connect to the modes of transportation they use to get to school.

The visits also generate valuable insights for the teacher who is then able to draw on them to support the growth of each student. As Beth notes, the visits allow her:

to see each host child in a totally different light. The Home Visits give the unique opportunity for the child who is quiet, shy, and reserved in school to really shine and be brave and take on a leadership role. I’ve had a few students who present as sort of “tough” or “aggressive” at school, and yet on the Home Visits, we see that they still sleep with their baby blankets, or have a special art table where they do watercolors, or sometimes have nightmares and need to sleep in their parents’ bed. It makes me realize even more than I already know, that all of my students don’t fit into just “one category.” I’ve found that having a deeper understanding of the students helps me to make stronger connections to school. It can be as simple as a book, for example, “I saw you have all the Peter Rabbit books at home, and we have some of the same ones,” or something like that. A student may be having a hard time with separation, and I learn on the Home Visit that they love Oobleck, so we’ll have Oobleck in class. Things like that.

Most importantly, the visits are transformative for the students. Again from Beth:

Home Visits are empowering for each student. Even if they’re not able to articulate it, each child on some level feels “Wow, I’m important enough to have a whole field trip just about me.” I think the visits really boost their confidence. They realize how lucky they are. They get to feel comfortable traveling around the city without their parents (this is a powerful learning opportunity for parents too!), they find meaningful (in the minds of 4- and 5-year olds) connections with each other, and they make new friendships that didn’t exist before the visits.

These journeys are integral to achieving our progressive mission and our diversity mission, allowing students to examine lives that they will never live through first-hand experience, our youngest students as participants in the most essential components of Elisabeth Irwin’s experiment.

Middle School Big Time

In developing the school’s original pedagogical methods (to support learning, Irwin and her colleagues saw immense value in work that connected ideas across subjects and that was framed by authentic inquiry in the service of meaningful projects undertaken by students. As Agnes De Limas notes:

We prefer to think of a curriculum not in terms of subject matter at all but rather in terms of experiences and activities. We assume the responsibility of seeing that before the child enters high school he shall have acquired the ordinary tools of learning and that we must help him to acquire them according to the best methods available. . . . We are, then, concerned in our curriculum to make sure that it affords the kind of experiences and the kinds of activities which will help children to grow normally and naturally. The old-line pedagogue was continually asking, What must a child know, what knowledge is of most worth? We ask instead, What should a child be like, what ways of acting and what habits of response are most worth while?” (pps. 16-17)

A collection of some of the essential questions generated by the middle school team as part of the process that led to the development of the BIg Time pilot:

A brief overview of the 2014 Innovation Institute that explored creative uses of time and from which the initial idea for Big Time emerged:

What follows are a collection of reflections from students and faculty on the value and challenges of the Big Time experiment:

Students:

I enjoyed having more time to work on things I needed more time on.

Maybe have it for a full day activity once a month

I think that big time worked well when the whole grade had a big project that we all had to work on. It was really helpful because it gave us a lot more time to work on projects.

I love big time! It’s really fun because now kids are leading them, and we always have fun. The only thing that could be better is that maybe kids could always lead them.

I like that we can be really creative and come up with really cool ideas. We can make interesting projects. Sometimes I don’t want to miss class though.

Big Time can be hard because I can’t focus on one thing for that long.

I like Big Time because it gives us time to learn more about the stuff we don’t know about. It’s also really cool when students run it because you get to watch your friends teach you!

I like Big Time. It gives everyone a time to work hard for a long time and get a lot of work done.

Learning Specialist Robin Shepard:

We saw kids over and over again learning from each other, creating peer groups (sometimes new and unexpected ones), and forming loosely organized groups that facilitated learning. After a few months, students were better at self-organizing and less and less structure was imposed. It was great to see them also develop their own language to explain what they learned. We heard kids say to peers things like: “But we didn’t finish this part; We should do it this way; What if…” It was easier for some kids to say to a peer, “Wait, I don’t get it,” than it was to say that to a teacher. There were more opportunities for reflective questioning coming from the kids not just the teachers, which led to more varied interpretations for kids to ponder.

Librarian Jennifer Hubert Swan:

As a middle school librarian who has to meet the reading and research needs of students across four grade levels, Big Time has been a salvation and a delight. It creates a consistent, weekly opportunity for me to collaborate with colleagues and support student work with library resources. Each week I can join any grade level team that is using the time to work on a large project and either lend my assistance or co-teach a mini research lesson or refresher.

Math teacher Michelle Boehm:

Having an extended period of time gave students the “brain space” to process and apply information. Students seem to feel more relaxed and curious about the work, and in feeling less pressed they were more inclined to ask the “what if” questions which sometimes led to a deeper exploration of an idea. There was also room for additional trial and error and Students were able to get feedback (from both peers and teachers) and make revisions in a timely manner. It was invaluable for students to see teachers from different disciplines working together to help them with their goals. Students also saw teachers as learners during Big Time and teachers were a bit more willing to take a risk and try a new activity knowing that colleagues were there to help execute and offer feedback.

Humanities Teacher Sara-Momii Roberts:

For the Eighth Grade Social Justice Project, students could dig into their topics, make phone calls and conduct interviews, go out of the building without the complication of scheduling these visits during other classes. Often, the creative process, the learning process, take stumbles and mental breaks and wrong turns and some wasted time. In the end, with longer periods dedicated to working on a particular project, students get to a better answer, a more creative result, and take a deeper dive into the learning. For many students doing this sustained work is hard. It’s also tricky for teachers to help steer the process and support extended focus on particular things. In many ways, extended periods go against modern day social interaction and ways of life. We don’t focus for long periods. Everything is quick and ready. So, helping students train themselves to do this is an important process.

Humanities teacher Sarah Barlow:

It helped to make interdisciplinary projects work, as teachers have time available to collaborate. For kids, It gives them longer periods to allow their creative and critical brains to latch on and engage in something rather than having fractured periods where they have to switch gears for each one.

Humanities teacher Dave Edson:

The extra time allows more wiggle room for differentiated learning, it allows for quieter students to get comfortable and step into leadership positions. Overall, the biggest benefit of extra time may be using the time to allow for more authentic student driven work, questions, and discoveries. This in turn allows for the work to be more creative and personal while working on their stamina and group work skills. I think it’s important to note that while Big Time is a longer than normal class period, what the students are being asked to do is often under a huge time constraint (in a positive way), it’s just that we’re tackling a bigger project. One Big Time approach has been to learn about something new or make a connection, make something with a new group of students, and share with the whole group. This means though that the clock is always ticking and students need to find agreement with each other and discover and implement smart, efficient ways of making their learning visible.

The middle school team is already at work thinking about what they learned from this year and iterating on the design of Big Time for next year. This focus on continually re-engaging the problem and taking smart risks is probably the most important aspect of this work and it is the one that aligns most closely with what students are asked to do each day in class. As Dave Edson observes,

Doing this work is sophisticated and just plain hard. This being said, nothing is perfect, nor does it need to be. There is some value in students planning for each other and then trying to figure out what to do when things don’t go according to plan, for good or bad. While teachers can provide a kind of template/outline for each other and for student led Big Time, ideally the whole experience still feels very worthwhile, even in its imperfections.

The Eleventh Grade Trip

In the spring of 2015, and stemming from LREI’s strategic plan LREI Director Phil Kassen posed two important questions to the high school faculty?

How might we create a weeklong overnight trip for our eleventh graders that is mission aligned, open to all, and embedded in the curriculum?

What if the entire junior class traveled to the city of Detroit and used the city as a lens to explore and learn about the challenges and opportunities of the modern urban city in transition?

While these were both questions of the moment, they were born out of LREI’s longstanding relationship with the field trip as an important tool for creating experience and opportunities for learning. As articulated by Agnes De Lima in The Little Red School House:

They need challenging tasks . . . . They are cramped by the four walls of the classroom and eager to explore the world beyond . . . . They enjoy the unexpected; it offers a test of their ability to deal with a situation. From our earliest days, trips have been an essential part of our school program; the curriculum is built around the children’s explorations of the world. We have referred also to the necessity on the teacher’s part of careful planning for these trips and the development of a technique which will insure safety, avoid strain and fatigue, and make certain that the children get all there is to be got from the excursion. No trip must be taken without long preparation. (pp. 95-96 & 153)

And as LREI Teacher Norman Studer also in The Little Red School House observes:

The usual trips for [high school] pupils have been to libraries and museums, worthy enough places but nevertheless repositories of embalmed culture. They do not afford the intellectual and emotional stimulation that comes from contact with the living book of man’s everyday life. . . . The Little Red School House has attempted to tear down the walls of the classroom and bring the adolescent child into direct contact with the community. . . . The most important outcome of all comes in terms of personality growth directly traceable to these trips. Children notoriously lacking in serious interests suddenly become interested in social problems. A feeling of kinship with people totally different began to develop. Their trips not only caused them to have an understanding of people but gave them the stimulus to do something about it. (pp. 158-160)

In response to Phil’s call to action, a planning team of interested high school faculty members was formed. The group enthusiastically jumped into the work of exploring Detroit as a destination, but also began to explore other possible cities. During this process, team members noted that the inquiry being carried out by the teachers would likely be work in which students could be productively engaged. That is, the adults should not debate the potential for learning by visiting various cities, reach consensus on a destination, prepare an itinerary and learning goals and then present this to the students as a fait accompli. This must be the work of the students, carried out with the support of their teachers. The group agreed, but also understood that going down this path invited a much higher degree of risk. Would the students be up to the task? Would they be able to meet the very real deadlines to ensure that there would, in fact, be a trip? High School Dean of Academics Allison Isbell was not fazed by these challenges. “This junior class is unbelievably strong, with many outstanding students and leaders,” Allison shared. “We knew they would have compelling ideas.”

Pivoting towards this new idea of a student designed experience, the team devised a series of trip labs for the fall. These labs created time and space for the eleventh graders to give voice to the important social issues that they saw as impacting their world and our nation’s cities. Then through a process involving brainstorming, research, debate, presentation, and consensus building, the students were called on to arrive at a set of organizing issues around which trips to one or more cities would be designed. Underlying this process was a project mission statement developed by trip coordinators Allison Isbell and Chris Keimig that stated:

Pivoting towards this new idea of a student designed experience, the team devised a series of trip labs for the fall. These labs created time and space for the eleventh graders to give voice to the important social issues that they saw as impacting their world and our nation’s cities. Then through a process involving brainstorming, research, debate, presentation, and consensus building, the students were called on to arrive at a set of organizing issues around which trips to one or more cities would be designed. Underlying this process was a project mission statement developed by trip coordinators Allison Isbell and Chris Keimig that stated:

Understanding one’s relationship to–and capacity to have an impact on–the most pressing challenges facing our society is a necessarily dynamic process. Thus, the best places to engage in this work are in places that are themselves dynamic–places that are in transition, that are working to change, adapt, and transform themselves for survival in a changing world. It is our purpose and mission at LREI to graduate citizens who are ready to engage in shaping their own communities, who believe in their capacity to affect change for the future, and who know that they can and should be a part of that process. We believe the time spent observing, learning about, and working alongside communities in transition is essential to cultivating these qualities in our students.

Later in the fall, the eleventh grade class gathered in the high school auditorium where eighteen pairs of students presented topics to their classmates. As the presentations unfolded, some students preferred their peers’ ideas and, in real time, dismissed their own. Then, employing flexible thinking, groups partnered with each other and created coalition-building opportunities around common goals. Eighteen teams were narrowed to ten, and then, through a survey process, to a final six, each to become the core focus of a trip comprised of 10-12 students. The six framing issues were:

- Refugee resettlement

- Sustainability and climate change

- Farm workers’ rights

- Educational equity

- Mass incarceration and criminal justice

- Urban revitalization

The issues identified, each team was then tasked with the challenge of developing an essential question to guide their trip and with researching three cities where their issue and its associated opportunities and challenges might be productively explored. Of their three cities, one had to be within driving distance and inquiry in all of their proposed destinations had to connect to both the school’s mission and the trip’s mission. Each team then presented their ideas to a panel of administrators who after weighing a variety of factors determined the destination city for each group. The final destinations were:

Students and teachers then began the complex task of reaching out to potential partners in their destination cities and developing an itinerary for the trip. In addition, each student took a history elective seminar that addressed in some way the larger themes connected to the trip. Finally, in the early hours of April 25, students and their teacher-mentors left via planes and vans for their various destinations and a week filled with learning. Below is a video produced by the group that traveled to Detroit to explore urban revitalization:

While each group explored different issues connected to different experiences, upon their return, students discovered a number of shared themes that emerged from these diverse experiences:

Stephanie (Justice for Farm Workers):

On the Monday when we got back from the trips, everyone was talking about the trips and even the people who weren’t really excited about the trips before we left were super excited. They were sharing a bunch of different stories and anecdotes about things that they learned, things that they saw and things that were unjust. I think that it really brought out hidden things for people. It made our classroom experiences so much richer because we weren’t just talking about English; we were making things connections to the trips. We were connecting the material we were learning with the experiences that we had. It was really able to integrate itself into our curriculum.

Tyrell (Equity in Education):

I’ve been going to LREI for 13 years and the trip definitely fulfilled the mission of the school — what we talk about and what we try to do. After the trip, I started an X-Block class called “Let’s Do Something for Social Justice.” The trip really motivated me to want to do something — to help make a change in the educational system. It was the best trip that I’ve been on and the most educational. Going into the trip I was like, “I’m going to change somebody’s life.” And then they told me that it was place-based learning and I said, “I don’t really know what that means.” But I realized after the first day that I had learned so much. I didn’t use Google once. I learned so much from just being there — experiencing it first hand. It was so great.

This LREI experiment in place-based studies could turn into a progressive education model for other secondary schools as well as colleges and universities. Allison remarks, “This process confirms that progressive pedagogy is alive and thriving in the hands of our students.” Chris continues, “This is the most progressive thing I’ve ever done as a teacher, and that our students have ever done. We took a real risk, and the payoff is going to be life-changing.”

What makes these experiences so powerful

While each of these projects provide a valuable window into the driving principles behind the LREI experience, one thing stands out across all three: these projects and their associated student learning and growth would not be possible without the dedicated time, energy and effort of LREI’s incredible faculty. Progressive teaching is complicated and demanding, but it is also joyful; and, as Elisabeth Irwin and her colleagues recognized almost one hundred years ago:

Our school, we feel is primarily made up of people, not of, instructors and pupils…. Our teachers are warm and vital human beings primarily concerned with human values and eager to discover with children how best these values may be fostered…. For this reason, we feel that progressive education lives not because of its theories or even its practices but because of the quality and caliber of its teachers. Primarily, of course, such teachers must understand children and be sensitive and responsive to their needs. They must be creative and inventive and resourceful; they must be stimulating, flexible, and fond of adventure…. Each teacher should look forward to the work that lies ahead and backward to what has gone before…. To be sure, each year a given ground should be covered in the academic subjects—adapted to the capacities and maturity of each group. But the program as a whole is constantly changing and emerging, growing out of experiences of the past, adapting to the present needs, and projecting into the future. (pps. 198-199 & 239)

True then and still true today.

References:

The Public and the Schools, 3-1-13; The New York Times, January 27, 1913

Lima, Agnes De. The Little Red School House. New York: Macmillan, 1942. Print.