The Power of Conversation: On the Diversity Director and Head Partnership

Originally published in the Summer 2014 issue of Independent School Magazine.

by Sandra (Chap) Chapman, with Phil Kassen

Since the late 1920s, diversity initiatives at the Little Red School House and Elisabeth Irwin High School (LREI) in New York City have centered on strategic conversations related to equity, justice, and inclusion. Culled from the writings by LREI’s founder, Elisabeth Irwin, are collaborative efforts with educators, social reformers, and politicians — all asking essential questions about the nature of the educational system of that era.

As the director of diversity and community at the school, I know my job is to build upon this historical foundation — particularly by nurturing authentic conversations about issues of identity and inclusion and posing questions that will help lead us to better policies and practices regarding diversity and community life. But as any diversity practitioner knows, none of this is possible — or not possible for long — without the complete support of the head of school.

It’s this relationship I want to focus on here. Phil Kassen, LREI’s head of school, and I decided that we needed to be conscious about how we build our working relationship. At the start of the 2012–2013 school year, we began a dialogue with each other about the personal stories — or “enough moments” — that impact how, as a team, we address the institution’s diversity and community needs. “Enough moments” is a term I first heard at an NAIS People of Color Conference workshop. It describes those moments from our past that shape our understanding of the world in regard to bias and discrimination — and which motivate us to get involved in social justice and equity work.

We believe so much in this exchange between diversity director and head of school that we crafted a workshop on the topic for the 2013 NAIS Annual Conference. What we offer here is a continuation of that dialogue. Much of it is based on the work of Juanita Brown and David Isaacs, senior affiliates at the MIT Center for Organizational Learning. In their 1996 article, “Conversation as a Core Business Process,” Brown and Isaacs focus on the importance of engaging in essential conversations within an institution.1 This got us thinking: What conversations can we bring to the surface that positively influence the diversity director and head partnership? Why are these conversations essential in creating programmatic and systemic changes in the school? Can the power of conversation help us develop mutual respect, build relationships across differences, and contribute to the creation of a shared diversity vision?

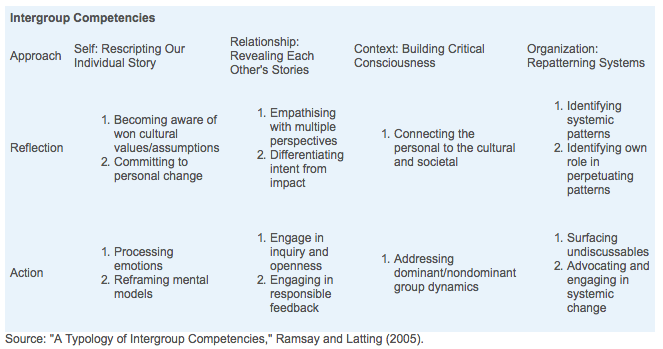

We also drew on the work of V. Jean Ramsey and Jean Kantambu Latting. In their article, “A Typology of Intergroup Competencies,” they suggest that we all practice 14 intergroup competency skills that can be applied across social differences with the goal of creating systemic changes.2 The skills (see sidebar below) are divided between two main components: reflection and action. The first stage requires us to self-reflect on our individual stories prior to engaging in conversations with others about their stories. Contextual skills follow as people learn to connect the personal to the cultural and societal. With these combined skills, we can then develop our organizational skills to collectively identify the systemic patterns that need addressing.

Because that description is abstract, we offer here short versions of our personal stories related to diversity issues — followed by an explanation of how sharing these stories has helped us build the foundation of our professional relationship and institutional change.

Sandra (Chap) Chapman’s Reflections

I grew up financially poor and culturally rich in Spanish Harlem in the 1970s and 1980s. My friends, neighbors, classmates, church, and community were primarily Puerto Rican and African American, with a sprinkling of people of Dominican and Mexican heritage. The nuns and priests of my Catholic elementary school were the only white people living in the area, except for one white boy in my class who left the neighborhood after third grade. I didn’t have white students in my class again until I attended a predominantly white Catholic high school in midtown Manhattan. High school was also the first time I got to know Asians, Haitians, Jamaicans, and South Americans beyond what I heard and absorbed from the media and society at large.

I heard many stereotypes about Asians and math, about poor blacks, and lazy Latinos, yet I also heard the frustrations from my friends who belonged to those groups. We sometimes joked about how naïve white people were for thinking such limiting thoughts about us, but we were never encouraged to talk about it outside of our circle of friends. Some of us developed relationships with the white kids in our grade, but racial separation predominated — and discussions about identity and culture in the curriculum did not exist. I never once heard a mention of black heroes or sheroes, nor a discussion about Latinos/as and immigration, nor about the contributions of Asian Americans. These limiting cultural and historical perspectives clouded the air I breathed throughout high school.

By the time I entered college, I was making sense of the racist comments coming from others, including my own parents about dark-skinned people, never mind that we had Latino/a relatives with dark skin. Between my late teens and young adulthood, I learned to see and operate in the world through a racial lens. The intersectionality of my identities — ethnicity, skin color, gender, budding sexual orientation, religion, and class — was ever present on my mind when I became an assistant teacher in my first independent school.

Fast forward to November 1991, and I am finishing up my first set of parent-teacher conferences as a new head teacher in an independent school in New York City. I will never forget this particular conference because the outcome of our discussion is one of the reasons I became an anti-bias educator. The African-American parents and their three-year-old daughter in that conference had experienced their first three months in an independent school, and they were concerned about their child’s racial identity. Their daughter was hitting all of her developmental milestones, and, so, while I was prepared to talk about her easy transition to an all-day threes’ program, I was equally anxious to speak to them about some comments their daughter had been making. This beautiful, brown-skinned African-American girl told me she wanted yellow skin, yellow hair, and blue eyes. The parents had heard the same comments at home.

From the start, the parents and I connected. We all grew up in Harlem in poor or working-class communities and were strongly linked to our rich cultural heritages. They were comforted knowing they were experiencing their first independent school outside of their community with a teacher of color and a handful of other students and families of color. Three months later, however, the dad wondered if they had made a grave mistake taking their child out of her community to expose her to so many white teachers and students at such a young age.

I naïvely thought that my personal background would suffice as a window into the experiences of poor or working-class families and families of color in a predominantly white school. No doubt my experiences with racism, sexism, classism, learning differences, and homophobia have given me credibility in conversations about identity issues. However, a missing component to my training as an educator was the skill needed to address bias when it surfaced in my classroom. Race, ethnicity, class, religion, and gender were rarely the focus of the many classes I took between my junior year in college, when I majored in a pre-education program, and graduate school. I began to wonder how I could have entered the field of education with plenty of early childhood development training under my belt, but with little to no knowledge about how to address social identity or inequities with young children.

Quite coincidently, authors on racial identity development and antibias education with young children were visitors to the school that year. These authors and their books — especially Beverly Daniel Tatum (Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations About Race,), and Louise Derman-Sparks (Anti-Bias Curriculum: Tools for Empowering Young Children) — shaped my personal views on education and put me on the path to becoming an antibias educator. I learned not to discredit my personal life experiences, but to add to my perspective a repertoire based on antibias training, which included understanding systems of oppression, identity development, multicultural education, and inclusive communities. I was beginning to gain the skills I needed to develop my own cultural competencies. This training proved useful when I became an administrator.

Another leap forward and we land at 2007. I have just accepted the position of director of diversity and community at LREI. The eight senior administrators at LREI had already experienced working for three years with a director of diversity and community. My predecessor had established an active parent SEED (Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity) group, supported a teachers of color group, gave voice to a parents of children of color group, initiated a parent training discussion on diversity initiatives, and structured faculty discussions with outside consultants, including diversity specialist Patricia Romney, white activist Tim Wise, and Kevin Jennings, a national voice on creating safe schools for LGBT people.

Between 2004 and 2007, LREI established a Diversity Task Force, which later became the Human Resources Committee, and drafted a Diversity Action Plan. In 2007, I joined this task force to refine and implement the action plan. By then, I had a growing understanding of the institution’s history regarding diversity work, but a more distant understanding of the needs or wishes of the head of school. I began to sense that, for me, meeting the institution’s needs would be aided by knowing more about the head of school.

Phil Kassen’s Reflections

As the school bus entered the driveway of Englewood Middle School, New Jersey, on the first day of sixth grade, it passed a flagpole on which flew the American flag and the school’s “Unity” flag — two clasped hands, one white and one a weird purplish brown. The same image was emblazoned on the floor mat as you entered the building. Looking back, I imagine that these grasping hands were designed to instill a sense of racial cohesion in a school riven by racial strife (the school system was still segregated only a few years earlier). It didn’t work. Those of us who were friends with children of other races in elementary school were not friends with them for long after the first day of middle school. As best as I can recall, the only exceptions were the talented African-American and white basketball players who hung out together.

Before I entered middle school, race was not something I thought about. I had African-American friends in elementary school, some of whom I considered to be among my closest friends. While I did not think about race or class at that time, in hindsight, I am sure that some of my friends did.

One incident stands out as the first race-based incident of which I was aware. When the first black family moved onto our block — a mom, dad, and a daughter named Crystal — their house was vandalized by the creepy old man of whom we were all afraid. For the white kids on the block, he was a mysterious presence about whom we shared neighborhood ghost stories. For Crystal, he was a real and true danger, nothing otherworldly about him. I heard about this situation, but there was no discussion — not at home, not in school.

In fact, the only conversation about race that I remember from my childhood was a comment made by my middle school shop teacher, Mr. Banks — a large, somewhat intimidating African-American man, serious to the point of severity. One day, he said, “If you white boys want the black boys to stop picking on you, just turn around and hit them in the face.” I don’t recall what precipitated this, but the message was clear: don’t seek unity — stand your ground and cement the lack of understanding that separates you.

My circuitous path to a community that embraced discussions of race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and other social identifiers continued for some time longer. My high school years were spent in an unabashedly bigoted high school where adults and children were intolerant and seemingly proud of it. The one African-American student in my freshman class left after three weeks. I followed this experience in intolerance, where I felt out of step, with a collegiate experience at a wildly liberal, inclusive school where I felt moderately unprepared to participate. However, as I gained some distance from my childhood experiences, I began to develop a desire to learn more about others, to develop the skills that would allow me to communicate, and to find a path to the unity that earlier experiences and communities lacked.

As the director of LREI, this desire still motivates me today. In particular, I look to my partnership with our director of diversity and community to puzzle through emergent issues and, more important, ensure that all decisions we make reflect the school’s diversity and social justice missions.

Creating a Team: Diversity and Head Partnership

As you can see, our backgrounds are different. But through our stories, we learned that we both were aware of racial segregation and tension in our lives. In particular, we could see how a primary institution for addressing the issue — school — was part of the problem. The silence about race that we both experienced growing up and our personal efforts to learn more in order to change the way schools address social injustice formed our common ground.

Knowing each other’s stories not only helps us to work together well, but also builds trust and encourages us to further develop our intergroup skills. In particular, we’ve developed and practice three cultural competency skills with each other in order to enhance our working relationship and better meet the diversity and equity needs of the school: (1) engage in inquiry and openness, (2) engage in responsible feedback, and (3) connect the personal to the cultural and societal.

Our first foray into this open dialogue occurred several years ago when we discussed racial microaggressions — both in the broader society and in our own community. We discussed what support looks like for adults of color; what the research says about the academic, social, and emotional needs of students of color attending predominantly white schools; and how important it was, given the culture’s relative silence on the topic, for Phil to embrace and talk about his white, male, and straight identities. Afterward, during diversity-related meetings, Phil engaged in exercises with other faculty members to address white privilege, power dynamics, institutional oppression, and the subtle ways people of color experience racism in the 21st century.

Because of our close working relationship, Phil trusted that the themes and consultants I brought to the school reflected the institution’s needs and were not part of any personal agenda. He also addressed diversity-related challenges and questions from members of the community through either private emails, public blogs, or speeches to the community. For example, after a mother of color was mistaken for being the babysitter of her light-skinned biracial son, Phil wrote a piece about how to handle racial assumptions, which he read to lower school parents as part of his welcome speech during curriculum night. It later became a permanent piece in our handbook to all new families.

As a diversity practitioner, I had to learn to separate the personal from the professional. This was not an easy thing to do when some of the roadblocks and microaggressions that community members shared with me were either ones I experienced or ones I did not want to encounter. However, with honest feedback from Phil about how to develop my administrative role, and having a safe space to vent without repercussion, we began to trust each other. This trust developed our ability to ask each other open questions and give honest feedback as it relates to enhancing LREI’s diversity initiatives. For me, improving the school’s inclusiveness and fighting for all forms of justice became easier to do knowing I had the support of the head of school.

A common complaint among diversity practitioners is that they are hired to bring about institutional change, and then feel as if the institution’s leadership is not supporting them in bringing about that change. Without a strong, open, and honest relationship with the head of school, diversity practitioners have little leverage — and lots of frustration. Schools talk about the importance of the relationship between the head of school and the board chair. But they also need to talk about the all-important relationship between the head and the director of diversity — and how it can best be developed.

Over the years, our partnership has had tremendous benefits for the institution. It has led to a greater openness in the community’s dialogue and discussion and has added tremendously to our social justice efforts. We are confident that if other heads of school and diversity practitioners focus on building their working relationship, they, too, will find uncommon success in an area of school life that continues to challenge us all.

Sandra (Chap) Chapman is the director of diversity and community, and Phil Kassen is head of school at Little Red School House and Elisabeth Irwin High School (New York).

Notes

1. Juanita Brown and David Isaacs, “Conversation as a Core Business Process,” The Systems Thinker Newsletter, 7(10), 1–6, 1996/1997.

2. V. Jean Ramsey and Jean Kantambu Latting, “A Typology of Intergroup Competencies,” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(3), 265–284, 2005.