“I was to discover that the line which separates a witness from an actor is a very thin line indeed; nevertheless, the line is real.” – James Baldwin

James Baldwin wrote the above words upon returning from a 1962 trip to Jackson, Mississippi, in which he witnessed firsthand the horrors of Jim Crow in the American south. The distinction he makes between being a witness to this struggle (“I was never in town to stay,” he writes) as opposed to an actor in it is one that he grappled with for some time after returning home to New York.

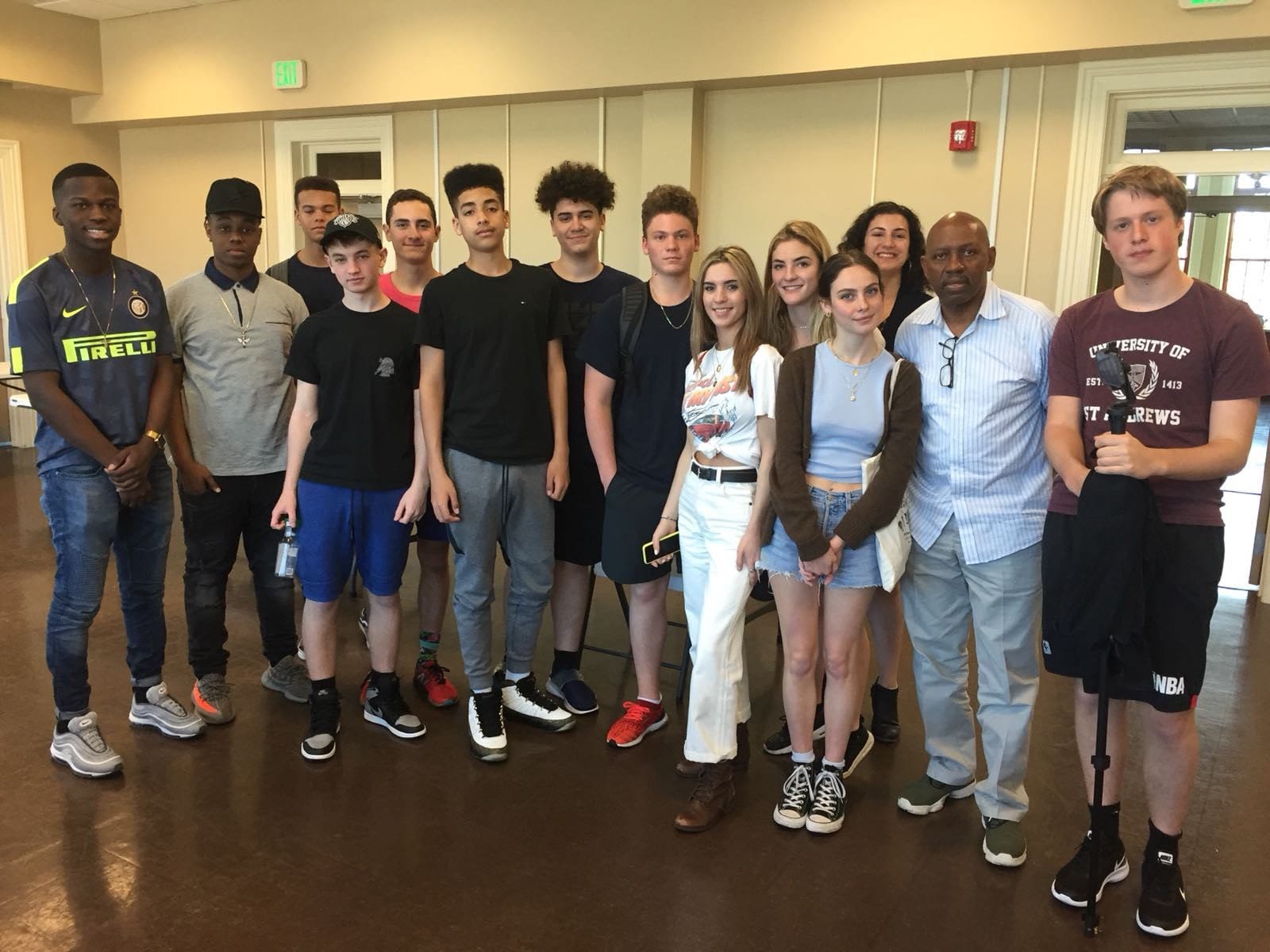

I was reminded of this quote last Monday morning as our juniors filed into the PAC on the first day back to school after their Junior Class Trips. They had had a powerful, immersive, and intense week away engaged in five different place-based research experiences across the U.S. (and, for the groups studying immigration, just beyond its borders as well): there were separate groups of students in Tucson and El Paso studying the past and present of immigration policy and its effects on the lives of people on both sides of the US-Mexico border; in Miami, examining the ways in which various aspects of our justice system (the courts, law enforcement, jails and prisons, and health care) conspire to criminalize mental illness; in New Orleans, studying the city’s police reform efforts and the relationship between law enforcement and mass incarceration of communities of color; and also in Miami, learning about the localized effects of climate change and the racial injustices that have been exacerbated in coastal communities as a result.

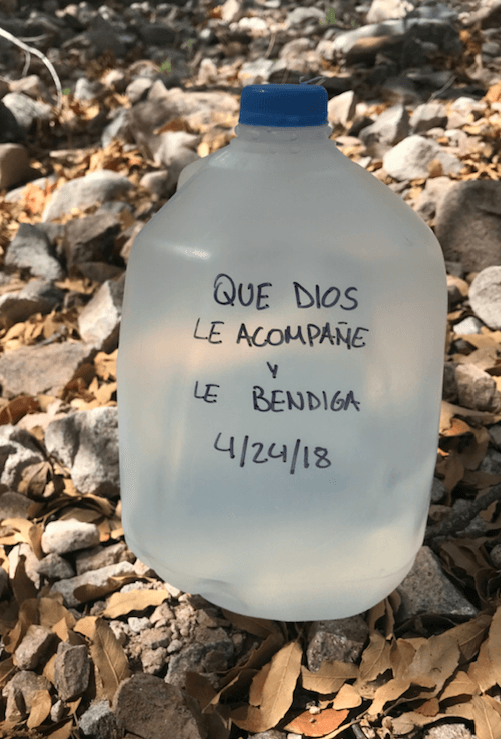

And not unlike Baldwin, our students returned from their trips with the overwhelming sense of having borne witness to an essential truth. They described their experiences and shared the stories of the people they met along the way: those of immigrants separated from their families and held indefinitely in ICE detention centers; of undocumented students whose education and safety remain under constant threat; of graduates of a felony diversion program in Miami’s mental health courts; of young people wrongly convicted of crimes and incarcerated for decades; of migrant workers whose homes and livelihoods are threatened by climate instability.

But our students recognized as well the privilege inherent in the role of the witness–the thin but real line that separates witness from actor–and they felt a certain anxiety at the prospect that they might eventually fold this experience all-too-neatly back into the routine and insulation of their daily lives. They felt, suddenly, the weight and urgency of their own responsibility to act in the face of the forces they confronted.

“We can choose to either keep on with this or choose to forget about it,” said one student in the PAC that first morning back. “But we all have a responsibility to do something with the privilege and knowledge that we have.”

“It’s up to us to humanize these unjust systems,” echoed another student.

Students spoke that morning of the possibility they saw in the power of their own collective action, of the obligation they had as citizens–as human beings–to share what they had learned and to dedicate themselves to working toward building a kinder, more humane, more just society.

Baldwin eventually comes to terms with his role as witness by confronting his own privilege and platform as a writer with a powerful voice:

“Part of my responsibility–as a witness–was to move as largely and freely as possible, to write the story and to get it out.”